Megan Bushnell, University of Oxford

[1] One of the most challenging aspects of studying Gavin Douglas is – paradoxically – the amount known about him. Thanks to the role he played in Scottish politics, more is known about Douglas’s life than those of his contemporaries (Bawcutt 1976: 1). His life can be rather neatly divided in two – the first part being devoted to poetry and learning, which yielded two great poetic works (Palice of Honour and Eneados), the second part devoted to his accruement of political power. The turning point is the Battle of Flodden, a crushing defeat for Scotland where James IV died. After the king’s death, Douglas’s nephew married the widowed Queen Margaret, gaining his uncle access to her beneficial patronage and the patronage of her brother, Henry VIII (Bawcutt 1976: 10-11). Douglas benefited greatly from this arrangement and became a figure of great power and influence in Scotland. However, he lost the Queen’s favour after his nephew’s marriage broke down (17-18) and fled to London to appeal to Cardinal Wolsey (20-22). He died there not long after in 1522 (22).

[2] Such a biography does not immediately conjure images of a patriot. Douglas often appealed to English authorities such as Queen Margaret, Henry VIII, Cardinal Wolsey, and even Lord Dacre – who fought for the English at Flodden, earned special hatred from the Scots for capturing James IV’s corpse (Brewer and Brodie 1920: 2913), and in whose house Douglas died (Bawcutt 2020-22: I.2) – demonstrating less a rejection of English political influence, but rather an embrace. In fact, Watt (1920: 1) accuses him of outright ‘disloyalty’ for pleading that Henry VIII enter Scotland, though he does not directly cite his source for this and no one else has repeated this claim. While it is true that Douglas cannot be so easily judged given the political situation of the time, his complex family history that ran the gamut from extreme patriotism to regicide (Royan 2012: 195-7), and his obligations to promote his family’s interests, it is fair to say that his status as a patriot must be heavily qualified. Nevertheless, scholars have at times claimed strongly that Douglas is a nationalist based on his recognition of Scots as a language in the Eneados, his translation of the Aeneid in proximity to Flodden, and his later professed fondness for the nationalist Gathelus and Scota myth. However, these cannot be read so straightforwardly.

[3] This paper seeks to contextualise Douglas’s apparent nationalism by focusing primarily on his written work, considering how nationhood is presented in the Eneados, with some reference to his earlier work the Palice of Honour (c. 1501). First it reflects on critical arguments concerning Douglas’s nationalism, especially those by Canitz (1996) and Corbett (c. 1999). This work then analyses Douglas’s characterisation of Scots and English within Prologue I of the Eneados and in his catalogue of notable authors in the Palice of Honour. Finally, this article examines how he depicts nationality within the body of his translation, using a combination of linguistic, computational, and literary analyses. The findings are that Douglas does have an interest in nationhood, but that this interest is not figured as especially polemical. Rather, his activities appear to be based on textual concerns rather than political ones. This sheds light on Douglas’s use of ‘Scots’ as a linguistic label and suggests a more symbolic usage of this term that is motivated primarily by literary anxieties. However, this usage does ultimately have nationalist consequences.

I. A Survey of Arguments Concerning Gavin Douglas’s Nationalism

[4] In Prologue I of the Eneados, Douglas declares that his book is ‘Writtin in the langage of Scottis natioun’ (2020-22: I.Prol.103) and refers to his language as ‘Scottis’ (I.Prol.118) – a distinction that he was ‘among the first to make’ (Bawcutt 1976: 37). Canitz (1996: 27) and Corbett (c. 1999: 41-42) have both described this statement as essentially nationalist – an out-an-out bid for linguistic self-determination. However, the linguistic situation at the time was not so clear-cut. At the time there was no clear indication that Scots was especially devalued or stigmatised in comparison to English (Bawcutt 1976: 37-38). Rather, Scots and English were considered the same language and called ‘Inglis’, whereas the main prevailing linguistic distinction was between English and Gaelic, or ‘Irische’ (McClure 1981: 52-53, 55). Even the most patriotic authors in Scotland – such as John Barbour (c. 1320-1395) and Blind Harry (c. 1440-1492), who wrote about the Scottish Wars of Independence – used this common terminology, belying the intrinsic nationalism of the term ‘Scottis’ (McClure 1981: 59). Rather the nationalist significance of this declaration appears to be a back projection from the later Scottish Renaissance movement in the twentieth century (Keller et al. 2014: 3).

[5] While the fact that Douglas makes this declaration on the eve of one of the most important battles between England and Scotland enhances its nationalist implications, Flodden also appears to be a red herring. There is no evidence that Douglas was a zealous proponent of James IV’s campaign of aggression against England. While he acknowledges that Virgil wrote the Aeneid in part to celebrate the Romans and promote Emperor Augustus (see Dearing 1952: 855), he makes no effort to claim to do the same for James IV. Rather he confines his observation of this to the Comment (Douglas 2020-22: n. I.v.102), making it more a matter of academic record than of narrative significance. Moreover, despite this propagandistic element, Virgil’s text is an odd choice for a pro-war stance, given that many critics have identified a ‘pessimistic outlook’ in the Aeneid that can be read as being anti-war (see Tarrant 1997: 184). Caughey (2009) argues that Douglas is sensitive to this critical voice, preserving it in his translation and arguably enhancing it in his Prologues, and that this might even be read ‘as a form of resistance against … the chivalric excesses of James IV’s court’ (262).

[6] While later in life, Douglas professes to have a great fondness for the Gathelus and Scota myth – which does actively apply the matter of Troy to the conflict between England and Scotland – this too is not necessarily solid evidence for Douglas’s political intentions when translating the Aeneid. The Gathelus and Scota myth traces Scotland’s origins to a Greek exile and an Egyptian princess and was used in the War of Historiography to counter England’s Brutus myth, which traced Britain’s origins to Brutus, the great-grandson of Aeneas, and was used ‘to justify [England’s] … incursions into Scotland’ (Simpson 1998: 398). This myth derived political strength by appealing to a Greek ancestor, the Greeks being the winning side in the Trojan war (Wingfield 2014: 10). Douglas’s interest in this myth could be evidence of his intentions to engage in the War of Historiography anew, giving his linguistic declaration in the Eneados extra significance. However, he does not make any attempt to invoke this myth in his translation (Cummings 1995: 143), despite how the Aeneid and the Scottish myth share the premise of exile and nation building (Simpson 1998: 399). In fact, he does almost the exact opposite and adopts a critical attitude to the Rutulians and their ‘furious passion’, even though, like the Scots in the Scottish Wars of Independence, they are fighting off an invading force (Caughey 2009: 275). Even the act of a Scotsman translating the Aeneid is strangely anti-nationalist, given England’s mythic connection to Aeneas (Wingfield 2014: 6). Moreover, given that Douglas expresses his interest in the myth almost a decade after the composition of the Eneados, it is unclear how much bearing it had on his translation.

[7] In this way, Douglas’s text does not appear to be pro-Scottish in the face of Flodden. Indeed, it is doubtful that Flodden figured extensively in Douglas’s decision to translate the Aeneid at all, but if it did, its influence likely manifested as a general interest in the Aeneid ‘as a way of making sense of the reality of war and as a guide to how it should be reasonably conducted’, rather than an outright allegory for Scotland’s political fortunes (Caughey 2009: 262). While the act of defining something as Scottish is intrinsically nationalist, his linguistic declaration cannot be understood as straightforwardly patriotic. Rather, many scholars argue that he considered nationhood through a literary and linguistic lens (Royan 2012: 197, 204; Wingfield 2014: 150-66). ‘Scottis’ in this context then may well describe the quality of Douglas’s translation more than his actual language. Consequently, it is important that Douglas’s texts be analysed – rather than his biography alone. To that end, this paper analyses Douglas’s texts with a view to better understand his ideas on nationhood and the intention behind his linguistic declaration.

II. Douglas’s Representation of Scottish Language and Literature

[8] Douglas’s first use of the term ‘Scottis’ occurs in his famous linguistic declaration in Prologue I of the Eneados:

Quharfor to hys nobilite and estait,

Quhat so it be, this buke I dedicait,

Writtin in the langage of Scottis natioun,

And thus I mak my protestatioun.

(1957-64: I.Prol.101-4)

Traditionally, scholars have mostly focused on the last two lines of this statement, but the first two lines are equally important, in that they elaborate on why Douglas feels the need to nationally define his language – he does so to correspond to the ‘nobilite and estait’ of his patron, specified earlier in the passage as ‘My speciall gud Lord Henry, Lord Sanct Clair’ (I.Pro.86). Douglas’s linguistic declaration is part of the dedication of his poem to Henry Sinclair (d. 1513) and should be read in that context.

[9] Douglas claims that he only dares to translate the Aeneid because Sinclair requested it, and Douglas felt obliged to fulfil this wish. This obligation is derived from two conditions. First, Douglas lists his kinship with Sinclair as a motivating factor, explaining ‘As neir coniunct to hys lordschip in blude / So that me thocht hys request ane command’ (1957-64: I.Pro.90-1). He then elaborates on Sinclair’s excellent character, declaring:

Quha mycht gaynsay a lord so gentill and kynd

That euer had ony curtasy in thar mynd,

Quhilk besyde hys innatyve pollecy

Humanyte, curage, fredome and chevalry

Bukis to recollect, to reid and se,

Haß gret delyte as euer had Ptholome?

(I.Pro.95-100)

[10] Later, in his Direction, Douglas reaffirms these two qualities, defending his translation by using Sinclair as a source for authority, based again on his family relations and character. He declares Sinclair to ‘be [his] scheld and defens’ (l. 11) and references Sinclair’s ‘Kyndneß of blude grundyt in natural law’ (l. 75) – ‘kyndneß’ signifying both ‘kinship’ and ‘The disposition or conduct of one of gentle birth’ (DSL: 1a, 3). He also promises to give to Sinclair anything that ‘afferis’ – or is suitable – ‘for [his] nobilyte’ (l. 78). He raises similar ideas of suitability in Prologue IX, where he emphasises how style must correspond with content, and the importance of ‘vassalage’ – which denotes both honour and the duties of someone in service to another (DSL: 1, 2) – declaring:

Eftir myne authouris wordis, we aucht tak tent

That baith accord, and bene conuenient,

The man, the sentens, and the knychtlyke stile,

Sen we mon carp of vassalage a quhile.

(Douglas 1957-64: IX.Pro.29-32)

[11] It is notable that he makes this claim in Prologue IX, as Book IX is the one book where Aeneas is absent from the narrative. Arguably, Douglas chooses to meditate on the ‘knychtlyke stile’ in response to this absence, as the Prologues present Aeneas’s journey as an allegory of Douglas’s own progress of translation, essentially figuring Aeneas as an analogue to Douglas’s translation method (see Ebin 1980). Likewise, Douglas’s description of Sinclair is evocative of that of Aeneas. He describes Sinclair as the pinnacle of nobility, attributing to him the qualities of ‘Humanyte, curage, fredome and chevalry’ (1957-64: I.Prol.98) and later attributes similar qualities to Aeneas, declaring that he portrays ‘euery vertu belangand a nobill man’ (I.Prol.325), including ‘All wirschip, manhed and nobilite’ (I.Prol.330). In this way, Sinclair is figured as a Scottish Aeneas, who likewise requires his text to be delivered in a form appropriate to his rank and character. He requires, in effect, a Scottish Aeneid.

[12] An English Aeneid is not a suitable offering for Sinclair; these already exist in the form of Caxton’s Eneydos (1490) and Chaucer’s Hous of Fame (1374-85) and Legend of Good Women (c. 1386), and Douglas makes it clear that these are not acceptable translations (1957-64: I.Pro.105-338). Indeed, these texts are not strictly speaking translations in the modern sense – they do not involve the direct translation of the Latin text into English. Rather, Caxton’s text adapts the Aeneid into prose through a French intermediary, and Chaucer’s texts are more poetic explorations of the abstract intertextual space of the Aeneid and other classical texts, rather than translations. Moreover, these texts place undo emphasis on the Dido episode – with Caxton distorting the proportions of the Aeneid, devoting, according to Douglas, 24 out of 65 chapters to Dido’s story (I.Pro.163-72) and Chaucer focusing only on this subject in the relevant section of the Legend of Good Women. This concentration on Dido is due to the influence of the romance tradition of reception of the Aeneid, which favoured loose adaptations that largely focused on Book IV and tended to be subversive of Virgil’s narrative (Baswell 1995: 11, 137, 185). Douglas objects to such subversion, especially when it results in the defamation of Aeneas’s character – as his defence of Aeneas (1957-64: I.Pro.411-49) demonstrates. Consequently, he goes to great lengths to distinguish his text from Chaucer’s and Caxton’s.

[13] He does this in a slightly different way for each author. For Caxton, Douglas repeatedly refers to his work as ‘Inglis’ or ‘Inglys groß’ (1957-64: I.Pro.138-9), in contrast to Douglas’s previous declaration that he writes in ‘Scottis’. In this way, he explicitly appeals to a separate literary tradition – one that Caxton is ostensibly not part of. By doing so, it is easier for Douglas to fend off the accusations inherent in English versions of the Aeneid. However, this separation is artificial, given how the Scottish and English literary traditions are interwoven. This is especially the case for Chaucer, whose influence on the Scottish Makars is so profound that they were commonly referred to as the ‘Scottish Chaucerians’ (Fox 1966). Consequently, Douglas’s approach to critiquing Chaucer differs from his approach for Caxton. Douglas does not criticise Chaucer based on his language, but rather his translation method, characterising it as a ‘word by word’ rendering (1957-64: I.Pro.345) – a claim that is demonstrably false, given that Chaucer’s texts are not close translations in any sense, and his own disdain for literal translation (Blyth 1987: 82). Instead, Douglas praises Chaucer’s language as ‘balmy, cundyt and dyall’ (1957-64: I.Pro.341), and surreptitiously refers to it as ‘our langage’ (359). Moreover, Douglas seems to include English in his understanding of Scots when he claims Virgil ‘stude … nevir weill in our tung endyte’ (I.Prol.494). While he could be referring to other Scottish interpretations of the Trojan myth (see Wingfield 2014), it seems more likely that he is referring to Caxton’s and Chaucer’s attempts. In this way, Douglas’s description of English and Scots and their relationship is somewhat contradictory and vague, where he appears both to argue for the difference between these languages and their literary legacies and emphasise their continuity.

[14] There is a similar effect in the Palice of Honour in the catalogue of authors resident at Venus’s court (Douglas 2018: ll. 895-924). This consists of three full stanzas outlining Latin, English, and Scottish authors. However, the stanzas are not split evenly across these groups. Rather, Latin authors receive two full stanzas, whereas the English and Scottish authors share just one, which serves to imply ‘the smallness of literary achievement in the vernacular compared to the multitude of those who wrote in Latin’ (Bawcutt 1977: 121). Moreover, while the Latin tradition is presented somewhat as a monolith, where medieval Italian poets like Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459; l. 901), Petrarch (1304-74; l. 903), and Boccaccio (1313-75; l. 915) are mixed in with ancient Roman poets like Plautus (c. 254-184 BC; l. 901), Valerius Flaccus (d. c. 90 AD; l. 903), and Claudian (c. 370 – c. 404 AD; l. 915), the English and Scottish authors are listed chronologically:

Yit thare I saw, of Brutus Albion,

Goffryd Chaucere as A per se, sance pere

In his wulgare, and morell John Gowere.

Lydgat the monk raid musand him allone.

Of this natioun I knew also anone

Gret Kennedy and Dunbar, yit undede,

And Quyntyne with ane huttok on his hede.

(Douglas 2018: ll. 918-24)

[15] First, the English authors are listed, who are all near contemporaries active in the late 1300s: Chaucer (c. 1340-1400), Gower (c. 1330-1408), and Lydgate (c. 1370 – c. 1451). Then the Scottish authors, who likewise are contemporaries active a century later: Kennedy (c. 1455-1508), Dunbar (c. 1459-1530), and Quintin, an unidentified poet listed as Kennedy’s ‘second’ in the Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy (c. 1500; Bawcutt 1977: 121). These are not necessarily the quintessential Scottish Makars as we perceive them today, but they would have been the most ‘prominent, indeed notorious, in Edinburgh literary circles’ at the time of Douglas’s writing (ibid). In this way, Douglas indicates a chronological continuity between the English and Scottish poets that feeds directly into the most recent poetic work of the day. However, he does not wholly conflate the two traditions, taking care to identify Chaucer, Gower, and Lydgate as ‘of Brutus Albion’ and Kennedy, Dunbar, and Quintin as ‘Of this natioun’ – i.e., Scotland.

[16] Such activity in both the Eneados and Palice of Honour indicates an eagerness to draw a distinction between England’s and Scotland’s literary and linguistic traditions, but also perhaps an anxiety about where this distinction lies, and a disinclination to repudiate the entire English canon, which is so closely entangled with the Scottish one. Consequently, the purpose and nature of this distinction is not wholly clear. Scots is uncertainly defined vis-à-vis its linguistic characteristics. Rather, it seems to have more to do with quality of translation. Consequently, perhaps the best course of action is to examine Douglas’s translation itself to see how he handles linguistic differences there.

III. Linguistic and Computational Analysis of the Eneados Using Digital Methods

[17] This paper combines distant reading with close reading, using data to identify general trends across the text as well as passages that would be fruitful for literary analysis. To enable this approach, a digitised version of the Eneados and its source text, Ascensius’s edition of the complete works of Virgil printed in Paris in 1501 (see Bawcutt 1973), was compiled and designed to be used with corpus linguistic tools – predominantly, AntConc (Anthony 2014), a freeware corpus analysis toolkit. This digital resource is in two formats – plain text and XML, a mark-up language that enables textual encoding. All thirteen Books and Prologues of the Eneados are included, along with the twelve books of the Aeneid (19 BC) and the Supplement (1428); Douglas’s Comment, book rubrics, and postscripts are not included, nor are the commentaries in Ascensius’s (1501) edition. The sources for these texts include Coldwell’s (1957-64) edition of the Eneados, Greenough and Kittredge’s (1897-1902) edition of the Aeneid, and Brinton’s (1930) edition of the Supplement, which are all available digitally. Greenough and Kittredge’s and Brinton’s editions were manually edited to reflect the orthography, punctuation, and ordinatio of Ascensius’s (1501) edition.

[18] As part of the digital resource’s XML files, there are several layers of annotation. The ones most relevant to this enquiry include pragmatic annotation, which demarcates narration and dialogue and identifies the gender, status, and nationality of every speaker; alignment annotation, which matches Latin lines in the Aeneid to their Scots equivalents in the Eneados; normalisation, which supplies standardised orthography to all lexical items in the Eneados; and part-of-speech and semantic tagging, which identifies the grammatical function and semantic category of every word. This was implemented using the USAS tagger (Rayson et al. 2004), which makes use of the CLAWS7 (1993-2014) and USAS (1990-2016) tagging sets. For more information about how these annotation systems were designed and implemented, please see Bushnell (2021a: 75-99).

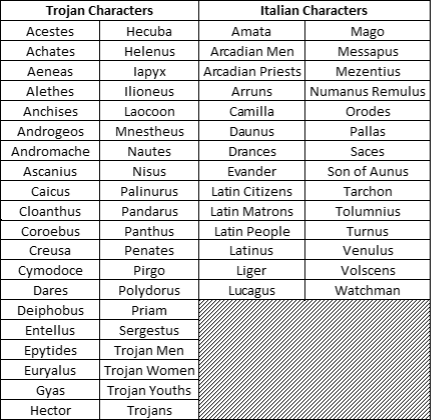

[19] Using this digital resource and annotation, this paper investigates the differences between how Douglas depicts the speech of citizens of the two nations with the most representation in the Aeneid – Troy and Italy. As previously explained, speakers throughout the Aeneid are identified by their nationality using pragmatic annotation. Using this annotation, it is possible to extract Trojan and Italian speech using XSLT – a coding language which can transform XML documents. Table 1 below lists which characters have been identified as a Trojan or Italian. The Italians are composed of citizens of several smaller kingdoms in Italy – such as Latium, Ardea, and Arcadia. Most gods are identified as having no nation, except for those who are clearly attached to a specific region or people, like the Trojans’ Penates or Tiberinus, god of the river Tiber.

Table 1: List of characters defined as being Trojan and Italian.

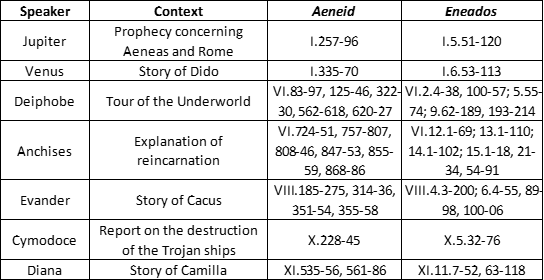

[20] Only direct speech is considered, with all incidents of reported speech excluded, except for Books II and III. Douglas presents these books as if they are being narrated by the translator-author, and not Aeneas, by moving the boundary between Books I and II (Royan 2015: 131-32). Consequently, Aeneas’s narrative in Books II and III, is treated as regular narrative, reported speech delivered by him is treated as regular speech, and reported speech nested in another instance of reported speech is discounted entirely. Narrative speeches – instances where characters recount a story – are also excluded, because narrative and speech have different linguistic characteristics, and these can obscure differences between types of speech (Labov and Waletzky 1967). See table 2 for a list of narrative speeches that have been excluded.

Table 2: List of narrative speeches excluded from this study.

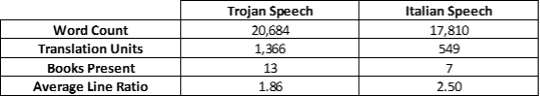

[21] Table 3 presents some basic statistics about the two types of speech, listing word count, the number of translation units in each group, the number of books that feature each type of speech, and the average line ratio in each group. A translation unit is defined as whole lines of the translation and source that are equivalent. Line ratios are calculated by dividing the number of Scots lines in each translation unit by the number of Latin lines within the same unit.

Table 3: Basic statistics for Trojan and Italian speech.

[22] Two analyses have been performed on Trojan and Italian speech. The first of these is a keyword analysis, performed in AntConc. The keyword tool compares two written samples and statistically determines if any lexical items, part-of-speech tags, or semantic tags are represented more often in one sample than the other. Results are determined by a log likelihood test, which compares the relative frequency of results between two samples (Brezina 2018: 72), and a Bonferroni correction, which compensates for the increase in probability that results will be found significant in error caused by performing numerous comparisons on a set of data (McDonald 2014: 257-9). The results are ranked by effect, measured by Hardie’s Log Ratio, which indicates how much more often a word appears in one block of text compared to another and emphasises larger differences (Hardie 2014). Higher effects indicate more substantial results; only effects greater than or equal to 0.5 are listed here.

[23] The second analysis performed is a computational analysis measuring the alignment of the translation to its source. The texts are aligned by line, so alignment can be measured by how many Scots lines are used to translate a single Latin line. This data has been collected for every single translation unit in the poem. Trends in this data are measured using a linear regression, a statistical model that predicts the value of a dependent variable based on an independent variable, or multiple independent variables in the case of multivariate linear regression (McDonald 2014: 191-249). These are tested using an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) which compares the variance between the groups being tested to the variance within each group (Brezina 2018: 192). An ANOVA can determine if there is a difference between groups, but it cannot reveal where the difference lies. This is revealed using a post-hoc Tukey test (194), which compares each of the means the ANOVA tested individually. ANOVAs and Tukey tests return a p-value, which indicates the probability that the distribution in a data set is random. A p-value less than 0.05 is indicative of strong results, signifying that there is a less than 5% chance that results are random. Where relevant, p-values are quoted here along with the test used to obtain them.

[24] The third analysis performed here consists of a close reading of specific passages in the Eneados that have been identified as relevant using a collocation search in AntConc to identify areas where labels of nationality have been used in proximity to other labels of nationality. This is helpful for identifying passages where Douglas is particularly concerned with the identification of characters’ countries of origin.

IV. Douglas’s Representation of Nationality within the Eneados

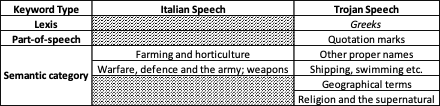

[25] The results of these three analyses reveal that Douglas does go to extra effort to distinguish between different nationalities in his translation of the Aeneid – though perhaps not in the way that might be expected, given previous claims about his interest in linguistic self-determination. Keyword analyses comparing Italians and Trojans (see Table 4) yield limited results. Syntactic differences are essentially non-existent. The lexical and semantic results are due to divergences in content between the two types of speakers as opposed to linguistic or stylistic differences implemented by Douglas. The Trojans sail around the Mediterranean (see Greeks, ‘shipping, swimming etc.’), visit different lands (see ‘other proper names’, ‘geographical terms’), and have many supernatural encounters (see ‘religion and the supernatural’). By contrast, the Italians exist in only two modes in the Aeneid – pastoral life and war. This is naturally reflected in the results (see ‘farming and horticulture’ and ‘warfare’).

Table 4: Results from three keyword analyses comparing normalised lexis, part-of-speech, and semantic tagging in Italian and Trojan speech.

[26] Similarly, Douglas does not distinguish Trojan and Italian speakers in translation method. In Book X, which features the most exchanges between the Trojans and Italians, the Italians Mago and Lucagus both interact with Aeneas, and all three share a similar pitch of discourse that utilises the same translation methods. Mago, for example, describes in detail the rewards he would give to Aeneas should Aeneas spare Mago’s life.

Caelati argenti: sunt auri pondera sacri:

Infectique mihi. non hic victoria teucrum

Vertitur: haud anima vna dabit discrimina tanta.

(Virgil 1501: X.527-9)

… Or charge of fyne siluer, in veschell quent

Forgyt and punsyt wonder craftely;

Ane huge weght of fynast gold tharby,

Oncunȝeit ȝit, ne nevir put in wark:

Sa thou me salf, thy pyssans is so stark,

The Troianys glory nor thar victory

Sall na thyng change nor dymynew tharby,

Nor a puyr sawle, thus hyngand in ballance,

May sik diuisioun mak nor discrepans.

(Douglas 1957-64: X.9.51-8)

[27] Douglas adds extensive content to his translation here, but it is usually inspired by what is already in the text – with only a few wholly original interpolations, such as ‘in veschell quent’, ‘Sa thou me salf, thy pyssans is so stark’, ‘thus hyngand in ballance’, which are still in the spirit of text and seem to be incorporated for the sake of rhyme and metre. Otherwise, his additions consist of synonyms and extra adjectives that are not represented in the Latin but are clearly inspired by the lexis and grammar. Examples include ‘fyne siluer’ for ‘argenti’, ‘forgyt and punsyt’ for ‘caelati’, ‘huge weght’ for ‘pondera’ and various other adverbs that communicate tone but not content – ‘wonder craftely’, ‘tharby’, ‘ȝit’, etc. This accumulation of language – reminiscent of the aureate style seen in Douglas’s Prologues and Palice of Honour – mimics the ornateness of the treasure that Mago is offering. Aeneas’s response is similarly inflated with original additions like ‘For thai na litill thyng tharby heß lost’ and ‘that rewthful harm, and that myschews cace’, which elaborate on what ‘hoc’ refers to. Douglas takes advantage of the repetition of ‘hoc’ to insert a synonymic doublet, creating a similar build-up of synonyms seen in Mago’s speech.

Hoc patris anchisae manes: hoc sentit iulus.

(Virgil 1501: X.534)

‘… That rewthfull harm, and that myschews cace,

Felys baith Ascanyus and my faderis gost,

For thai na litill thyng tharby heß lost’.

(Douglas 1957-64: X.9.68-70)

[28] There is a similar interaction later between Lucagus and Aeneas. Like Mago, Lucagus begs Aeneas for mercy – although he appeals to Aeneas’s good nature rather than attempting to bribe him. Again, the expansions heighten the emotional pitch of Lucagus’s plea, enumerating many reasons why he should be spared. Like Mago, his speech is full of elaborative expansions and synonyms (see ‘thy thewys’ and ‘thy parentis’ for ‘parentes’, ‘wofull sylly sawle’ for ‘animam’, and ‘maist of renowne’, which has no equivalent in the text). Again, Aeneas responds with a similar level of interpolation: ‘Syk sawys war langer furth of thy mind’ is an original addition, ‘all hym allane’ is derived from ‘desere’, ‘the behuffis’ makes explicit the imperative force of ‘morere’.

Lucagus:

Per te per qui te talem genuere parentes

ir troiane: sine hanc animam: et miserere precantis.

(Virgil 1501: X.597-8)

‘O Troiane prynce, I lawly the beseik,

Be thyne awyn vertuus and thy thewys meyk,

And be thy parentis maist of renowne,

That sik a child engendryt heß as the,

Thow spair this wofull sylly sawle at lest,

Haue rewth of me, and admyt my request’.

(Douglas 1957-64: X.10.121-6)

Aeneas:

… morere et fratrem ne desere frater.

(Virgil 1501: X.600)

‘Syk sawys war langer furth of thy mynd.

Sterve the behuffis, less than thou war onkynd

As for toleif thy broder desolait

All hym allane, na follow the sam gait’.

(Douglas 1957-64: X.10.129-32)

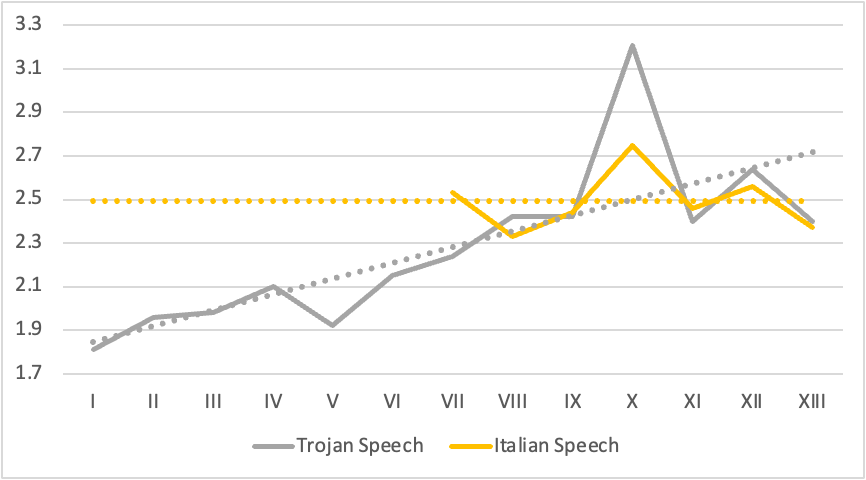

[29] In this way, Douglas does not appear to differentiate between characters of differing nations when translating their exchanges. Beyond the knowledge that Mago and Lucagus are fighting against Aeneas, there is no indication in their speech that they are different from Aeneas. They pursue a similar type of translation – namely one that follows the syntax of the Latin closely, though not rigidly, and attempts to translate every word without significant paraphrase or elision. There is also a similar level of expansion in both translations, as confirmed by a multivariate analysis of line ratios in the Eneados (see Figure 1). While a two-way ANOVA indicates that character nationality is a conditioning factor in rates of expansion in character speech, a Tukey Test reveals that this is only a significant factor for characters who have no nation – i.e., gods, whose speech is consistently expanded upon to a lesser degree throughout the poem. The Tukey Test finds no significant difference between Trojan and Italian characters – nor between characters of any other named nation (i.e., Greece and Neutral, which includes Carthage, Cumae, and Getulia).

Figure 1: Average line ratios for Italian and Trojan speakers over the course of the ‘Eneados’. The effect of nation is significant according to a multivariate linear regression tested by a two-way ANOVA (p < 0.001) but is not confirmed by post-hoc Tukey test (p = 0.70).

[30] These results are not necessarily surprising, given that Virgil himself does not distinguish between the characters of these nations linguistically. While the Aeneid features numerous interactions between Trojans, Greeks, Italians, and Phoenicians, Virgil depicts all his characters as being mutually intelligible to one another without need of interpreter. More than that, he depicts them all speaking the same language – Latin – and does not try to characterise different nations with different types of speech, even though he implies that these other discourses exist, given Juno’s final request to Jupiter that the Italian people retain their own language (Virgil 1501: XII.819-28; Douglas 1957-64: XII.13.69-90). Rather, he uses allusions to the work of other Greek and Roman poets as a form of characterisation – especially with Aeneas, whose speech frequently alludes to Odyssean and Achillean dialogue (Highet 1972: 187-8) – and is very calculated in his decisions as to who speaks, where, and how much. Given that Virgil is primarily focused on a few core characters (21-23), it is perhaps unfair to expect there to be representation of language differences between nationalities – especially for the depiction of a story that was already considered an ancient legend. However, what is interesting here is that Douglas does not alter the text to highlight his own interest in language, as implied by his linguistic declaration in his Prologue. He does not use the Aeneid to explore how linguistic differences between two closely intertwined cultures are manifested by their speakers. Nor does he use it to re-enact Scotland’s mythic past by casting the Trojans as the English or the Italians and Greeks as the Scots. He in no way manipulates the speech of characters to explore the concept of nationality.

[31] However, the same cannot be said for narrative. When narrating battle scenes, Douglas frequently makes explicit character’s nationalities where Virgil preferred to leave everyone unlabelled. For example, in Book IX Douglas transforms a one-line catalogue of the dead and victorious into four lines highlighting where everyone is from. For Virgil the focus is on individuals killing other individuals, with no sense of net benefit, but Douglas gives this carnage a purpose by making nationhood explicit.

mathiona liger: chorineum sternit asylas …

(Virgil 1501: IX.571)

Liger a Troiane from the wall also

Doun bet a Rutiliane hait Emathio.

A Phrigiane eik, Asylas, stern and stowt,

All tofruschit Choryneus withowt

(Douglas 1957-64: IX.9.99-102)

[32] This might not seem like an important alteration, but it must have required effort. The Aeneid includes many characters that are mentioned only once and whose nationality is not always identified. To add this material, Douglas must have researched each character in various commentaries. For example, Ascensius offers the following explanation for the previous lines:

Liger id est vt videtur italus quasi ligur aut ligus id est de luguria sternit emathiona id est troianum illum et id quidem vocabula indicant: sed series verborum postulare videtur vt dicamus liger scilicet troianus ille sternit emathiona scilicet rutulum: nam is proprie sternit qui desuper incumbit vt itali non rutuli. Asylas troianus: sternit chorineum italum hic scilicet chorineus erat super: … (Ascensius 1501: 288v)

Liger – seems Italian like the names Ligur or Ligus, i.e., from Liguria – kills Emathio, a Trojan man; at least this is what the vocabulary indicates. But it seems that the order of words demands that we say Liger, a Trojan, kills Emathio, a Rutulian. For, properly, the one mentioned last kills the one who is mentioned before – as they are Italians, not Rutulians. Asylas is a Trojan; he kills Chorineus, an Italian, here, because Chorineus was listed before.

(Bushnell translation)

[33] Douglas follows Ascensius’s instruction here in making Liger and Asylas Trojans, and Emathio and Chorineus Italians. However, the explanation Ascensius provides is odd. By etymology he suggests that Liger and Asylas should be identified as Italians, but he argues that word order dictates against this. However, it is not entirely clear why the syntax should reflect upon these characters’ nationalities. Rather, the word order only indicates who is the object and who is the subject – i.e., who is killed and who does the killing. Ascensius’s claim that word order also implies nationality indicates that the conclusion here is foregone: Liger must be a Trojan, because he kills Emathio, and it is the Trojans who ultimately win. However, there is no sense of Trojan victory in the original text at this point. Rather, it is the Italians who are besieging the Trojans, so Ascensius’s interpretation of grammar here is rather extraordinary. The fact that Douglas uses this interpretation suggests a similar desire to foreshadow that it is the Trojans who ultimately win.

[34] There are many other examples of this tendency to make nationhood explicit – every book featuring a major battle has a similar passage (see Virgil 1501: II.425-6, Douglas 1957-64: II.7.111-3; Virgil 1501: X.753-4, Douglas 1957-64: X.12.157-62; Virgil 1501: XI.612, Douglas 1957-64: XI.12.37-8; and Virgil 1501: XII.371, Douglas 1957-64: XII.6.147-9). The exception is Book VII, potentially because this book does not involve proper armed combat between the two nations, but an unofficial skirmish between a Trojan hunting party and Latin shepherds. By contrast, Book IV has an example, even though there is no battle scene, where Douglas reminds us that Aeneas and Dido are representatives of their nations (see Virgil 1501: IV.60, Douglas 1957-64: IV.2.16-7), and consequently their love affair is a geopolitical issue. In this way, Douglas employs this hyper-attention to nationhood only when nations are coming into conflict in an official capacity. Crucially, he does not interpret this conflict in terms of difference. Rather, like Virgil, he aligns speakers of different nations so that they all use the same discourse. However, he makes extra effort to specify that they come from diverse places.

V. What’s in a Name?

[35] In summary, Douglas’s approach to translating the concept of nationality in the Aeneid does not especially adhere to ideas of patriotism and nationalism – at least in the way they are understood today. Douglas does not turn the Aeneid into an allegory concerning Flodden, nor does he use it to explore how identity is manifested in individuals’ speech. Rather, his meticulous approach to the text suggests that he would have found such manipulation of the text inappropriate, which implies that he translated the Aeneid for other reasons. These reasons seem to be primarily a respect for the text, an idea of what accuracy in translation entails, and a desire to engage in scholarly discourse, which are ideas more congruent with humanism than nationalism.

[36] However, that is not to say that Douglas is wholly uninterested in nationalism, or that his translation does not have political weight. Nation matters enough that Douglas frequently specifies characters’ nationalities in battle scenes. However, he does not indicate that one nation is by its nature superior to another. Rather, Douglas has an interest in what nationhood means generally, as opposed to the value of a specific nationality. His concern is not which nation is morally superior but that the Trojan refugees find a new nationality – that they find Rome. The implication is that having a nation is better than having no nation, in that it gives purpose to what would otherwise be pointless carnage. Such an alteration may appear small, but it removes the ambiguity in the Aeneid, where Virgil constantly prompts the reader to question whether Rome is worth the human cost (Tarrant 1997: 177-82). While Douglas does not valorise war (Caughey 2009), there is never a sense of futility in his version of the Aeneid. There is no question about the value of Rome.

[37] For Douglas, Rome is the foundation of the political structures of western Europe and western Christendom (Hamilton 2000: 115). The Aeneid, therefore, in recounting the mythic founding of Rome, is rife with political significance. It is a text inherently about nation-building, both in terms of armed conflict and linguistic and literary self-determination, in that it also relates the implementation of Latin as the national language of Rome and provides a model of cultural translation through its adaptation of numerous elements of the Homeric epics (Farrell 1997). Consequently, when Douglas translates the Aeneid, he is not just translating a text into Scots but rather an entire method of navigating cultural differences. This becomes apparent in various aspects of Douglas’s translation, such as his Prologues that reinterpret moments in the Aeneid as developments in his own poetic evolution; his casting of Sinclair as both an Aeneas- and Maecenas-figure, who was Virgil’s patron and ‘the image of a model sponsor’ (Wilson-Okamura 2010: 60); his declaration that he writes in Scots, just as Juno begs Jupiter that the Trojans and Italians adopt the Latin language. In this way, Douglas strives to be accurate not only to Virgil’s text but to his entire process. However, his method does differ obviously in one way in that his translation revolves around the idea of homage, rather than displacement – at least for the Latin. Rather, he uses Virgil’s model of artistic reinvention for English sources, misrepresenting Chaucer’s attitudes towards translation, and distilling many Chaucerian and Lydgatian poetic forms and turns of phrase into his paratext and Book XIII (Bawcutt 1970).

[38] The overall effect is that Douglas figures Scots – not English – as the successor to Latin, and makes access to a complete, accurate, almost academic translation of the Aeneid contingent on being able to read Scots. Such an action clearly has political implications; however, these do not appear to be aggressive or propagandistic, given that Douglas does not in any way allude to England and Scotland’s own political circumstances otherwise. Rather, his declaration to write in Scots appears to be an assertion of confidence after a century of successive poetic talents starting with James I (1394-1437) and the Kingis Quair (c. 1423). McClure (1981: 58) discusses the idea of ‘apperceptional languages’, whose differences are only apparent to their speakers. This may be a case of ‘apperceptional literatures’, whose differences only became apparent to Douglas, partly because he is at the tail end of this productive period, and partly due to the political nature of the text he translated.

[39] The label ‘Scots’ then was productive for the development of a poetic medium suitable for the translation of a text concerned with themes of language, identity, and statesmanship. t relocates Douglas’s work to a different canon – one that has not been appealed to before explicitly — so he is able to build it from scratch. He does this work in his paratext, using a variety of different poetic models in his Prologues, ranging from aureate to alliterative poetry built on both Scottish and English models, and referencing a multitude of Latin sources in his Comment. Likewise, his language draws from a variety of sources. While he describes his language as Scots ‘braid and plane, / Kepand na sudron bot our awyn langage, / And spekis as I lernyt quhen I was page’ (1957-64: I.Prol.110-2), he quickly contradicts this statement saying ‘Nor ȝit sa cleyn all sudron I refuß’ (I.Prol.113) and admits that he makes use of ‘Sum bastard Latyn, French or Inglys oyß’ (I.Prol.117). He justifies this lapse by comparing it to how Latin sometimes uses Greek vocabulary (I.Prol.115), adopting again stylistic strategies from Latin into his own poetic style.

[40] Moreover, in using Sinclair as the spokesman for Scots, Douglas implicitly ties Scots to the ideas of kinship and moral excellence – two of the dominant themes in the Aeneid. In this way, the declaration that he writes in ‘Scots’ is more in service to the content of his text rather than in service of a political agenda. While it undoubtedly has a nationalistic force, the root of this is not obviously in his own patriotic feeling. Rather, it seems to be a natural progression of his development of his translation method while working on the Eneados. For Douglas, nations are figured as textual traditions and ways of reading. These become figured as linguistic differences because translation and reading are analogous processes and because Douglas emphasises accurate linguistic representation in his translation method. In this way, as Royan (2012: 207) argues, ‘For Douglas, identity rests more in language and literature than narratives of violence’.

Works Cited

Incunabula

Virgil. 1501. Opera cum variorum commentariis,ed. by Jodocus Badius Ascensius (Paris: Ascensius & Jean Petit). UB Freiburg, Freiburg, Ink 4. D 7672, in Freiburger historiche Bestände—digital <http://dl.ub.uni-freiburg.de/diglit/vergilius1500>; [accessed 8 January 2021].

Primary Sources

Brewer, J.S. (ed.). 1920. Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 21 vols (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts), in British History Online [accessed 4 December 2022].

Douglas, Gavin. 1957-64. Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’ Translated into Scottish Verse by Gavin Douglas, ed. by D.F.C. Coldwell, Scottish Text Society, 3rd Series, 30, 25, 27, 28, 4 vols (Edinburgh: Blackwood), in Literature Online [accessed 7 January 2021].

———. 2018. The Palyce of Honour, ed. by D. Parkinson, Middle English Texts (Kalamazoo, MI: Published for TEAMS Teaching Association for Medieval Studies in Association with the University of Rochester by Medieval Institute Publications, in TEAMS Middle English Texts; [accessed 1 February 2021].

———. 2020. The ‘Eneados’: Gavin Douglas’s Translation of Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’, ed. by P. Bawcutt with I. Cunningham, Scottish Text Society, 5th Series, 17, 18, 19, 3 vols (Edinburgh: Scottish Text Society).

Vegio, Maffeo. 1930. Maphaeus Vegius and his Thirteenth Book of the ‘Aeneid’: A Chapter on Virgil in the Renaissance, ed. by A.C. Brinton (Stanford: Stanford University Press), in Virgil.org [accessed 4 January 2021].

Virgil. 1897-1902. The Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics of Virgil, ed. by J.B. Greenough and G.L. Kittredge, 2 vols (Boston: Ginn), in Perseus Digital Library [accessed 7 January 2021].

Digital Resources

Anthony, L. 2014. AntConc, version3.4.4.w, Windows/Linux/Mac (Tokyo: Waseda University) [accessed 4 January 2021].

———. 2020. AntConc, version3.5.9, Windows/Linux/Mac (Tokyo: Waseda University) [accessed 4 December 2022].

DSL: Dictionary of the Scots Language (Glasgow: University of Glasgow) [accessed 8 January 2021].

Rayson, P., D. Archer, S. Piao, T. McEnery. 2004. ‘The UCREL Semantic Analysis System’, in proceedings of the Workshop on Beyond Named Entity Recognition – Semantic Labelling for NLP Tasks (Lisbon: 4th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation), pp. 7-12 [accessed 4 December 2022].

‘UCREL CLAWS7 Tagset’. 1993-2014. UCREL: University Centre for Computer Corpus Research on Language (Lancaster: University of Lancaster) [accessed 6 January 2021].

‘USAS Semantic Tagset’. [1990-2016]. UCREL: University Centre for Computer Corpus Research on Language (Lancaster: University of Lancaster) [accessed 8 January 2021].

Unpublished Theses

Bushnell, M. 2021. ‘Equivalency, Page Design, and Corpus Linguistics: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Gavin Douglas’s Eneados’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Oxford).

Secondary Sources

Baswell, C. 1995. Virgil in Medieval England: Figuring the ‘Aeneid’ from the Twelfth Century to Chaucer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Bawcutt, P. 1970. ‘Gavin Douglas and Chaucer’, The Review of English Studies, 21.84, 401-21.

———. 1973. ‘Gavin Douglas and the Text of Virgil’, Edinburgh Bibliographical Transactions, 4.6, 211-31.

———. 1976. Gavin Douglas: A Critical Study (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press).

———. 1977. ‘The “Library” of Gavin Douglas’, in Bards and Makars: Scottish Language and Literature: Medieval and Renaissance, ed. by A.J. Aitken, M.P. McDiarmid, and D.S. Thomson (Glasgow: University of Glasgow Press), pp. 107-26.

Blyth, C.R. 1987. ‘The Knychtlyke Stile’: A Study of Gavin Douglas’s ‘Aeneid’ (New York: Garland).

Brezina, V. 2018. Statistics in Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Guide (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Canitz, A.E.C. 1996. ‘“In our awyn langage”: The Nationalist Agenda of Gavin Douglas’s Eneados’, Vergilius, 42, 25-37.

Caughey, A. 2009. ‘“The Wild Fury of Turnus Now Lies Slain”: Love, War and the Medieval Other in Gavin Douglas’s Eneados’, in Masculinity and the Other: Historical Perspectives, ed. by H. Elllis and J. Meyer (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), pp. 261-80.

Corbett, J. c. 1999. Written in the Language of the Scottish Nation: A History of Literary Translation into Scots (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters).

Cummings, R. 1995. ‘“To the cart the fift quheill”: Gavin Douglas’s Humanist Supplement to the Eneados’, Translation and Literature, 4.2, 133-56.

Dearing, B. 1952. ‘Gavin Douglas’s Eneados: A Reinterpretation’, PMLA, 67.5, 845-62.

Ebin, L.A. 1980. ‘The Role of the Narrator in the Prologues to Gavin Douglas’s Eneados’, The Chaucer Review, 14.4, 353-65.

Farrell, J. 1997. ‘The Virgilian intertext’, in The Cambridge Companion to Virgil, ed. by C. Martindale (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge), pp. 222-38.

Fox, D. 1966. ‘The Scottish Chaucerians’, in Chaucer and Chaucerians: Critical Studies in Middle English Literature, ed. by D. Brewer (London: Nelson), pp. 164-200.

Hamilton, D. 2000. ‘Re-Engineering Virgil: The Tempest and the Printed English Aeneid’, in ‘The Tempest’ and its Travels, ed. by P. Hulme and W.H. Sherman (London: Reaktion), pp. 114-20.

Hardie, A. 2014. ‘Log Ratio – an Informal Introduction’, ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science (CASS) <http://cass.lancs.ac.uk/log-ratio-an-informal-introduction/> [accessed 5 January 2021].

Highet, G. 1972. The Speeches in Vergil’s ‘Aeneid’ (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Keller, W.R., J.D. McClure, and K. Sandrock. 2014. ‘Introduction: Scottish Renaissances’, European Journal of English Studies, 18.1, 1-10.

Labov, W. and J. Waletzky. 1967. ‘Narrative Analysis: Oral Versions of Personal Experience’, in Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts: Proceedings of the 1966 Annual Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society, ed. by J. Helm (Seattle: American Ethnological Society, University of Washington Press), pp. 12-44.

McClure, J.D. 1981. ‘Scottis, Inglis, Suddroun: Language Labels and Language Attitudes’, in Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Scottish Language and Literature (Medieval and Renaissance), ed. by R.J. Lyall and F. Riddy (Stirling: University of Stirling; Glasgow: University of Glasgow), pp. 52-69.

McDonald, J.H. 2014. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 3rd edition (Baltimore: Sparky House Publishing) <https://www.biostathandbook.com/HandbookBioStatThird.pdf> [accessed 4 December 2022].

Royan, N. 2012. ‘The Scottish Identity of Gavin Douglas’, in The Anglo-Scottish Border and the Shaping of Identity, 1300-1600, ed. by M.P. Bruce and K.H. Terrell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 195-209.

———. 2015. ‘Gavin Douglas’s Humanist Identities’, Medievalia et Humanistica: Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Culture, n.s., 41, 119-36.

Simpson, J. 1998. ‘The Other Book of Troy: Guido delle Colonne’s Historia destructionis Troiae in Fourteenth- and Fifteenth-Century England’, Speculum, 73.2, 397-423.

Tarrant, R.J. 1997. ‘Poetry and power: Virgil’s poetry in contemporary context’, in The Cambridge Companion to Virgil, ed. by C. Martindale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 169-87.

Watt, L.M. 1920. Douglas’s Aeneid (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Wilson-Okamura, D.S. 2010. Virgil in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Wingfield, E. 2014. The Trojan Legend in Medieval Scottish Literature (Cambridge: Brewer).