Emily Winerock

Introduction

[1] The exact characteristics of a witch were contested in early modern Europe. Was the primary danger spiritual, as George Gifford argued in Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcrafts (1593), or could witches physically harm their victims, as King James VI of Scotland (and future king of England) argued in his treatise Daemonologie (1597) (Maxwell-Stuart 2020: 174–5)? For centuries, English witches had primarily spent their time on maleficium, magical acts intended to cause harm to people or property, such as causing bad weather and making people and livestock ill. However, during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, English witches were increasingly assumed to have adopted continental European witches’ rather more colourful extra-curriculars, such as copulating with the Devil and his demons and dancing and feasting at the witches’ Sabbath (Blécourt 2013: 93). Interrogators in English witchcraft trials made it clear through their questions that diabolical celebrating was expected of ‘true’ witches, along with flying on broomsticks, having a familiar, and pledging devotion or selling one’s soul to Satan, perhaps with an osculum infame or Devil’s kiss (See Fig. 1).[i]

[2] Therefore, one might assume that when Renaissance witches danced, they did so in a lewd or lascivious manner. Certainly, early modern commentators spent a great deal of time and ink on warnings about the moral dangers of dancing (Arcangeli 1994: 127–55; Pennino-Baskerville 1991: 475–94; Wagner 1997: 19–44). For example, Phillip Stubbes calls dancing ‘the root of all filthynes and vncleannes’ in The Anatomie of Abuses (1583: Book I, sig. D2r). John Northbrooke asserts that dancing schools are essentially ‘houses of baudrie’ for the lust and lechery they generate in students (1577: 166). Even playwrights and poets acknowledged the moral perils of dancing: Thomas Dekker quips that lechery is the patron of vaulting houses and dancing schools in The Seven Deadly Sins of London (1606: 2.52; Williams 2001: 366), while Thomas Nashe refers to the brothel as a ‘dancing-schoole’ in his erotic poem Choise of Valentines (c.1593: 3.407; Williams 2001: 366).

[3] Several commentators specifically associated dancing with the Devil. Gervase Babington writes that dancing is ‘an olde practise of the deuil to occupy men withall’, ‘an ancient exercise of the wicked’, and ‘the chiefest mischiefe of all’ (1583: 318). Explicitly linking immodest dancing with damnation, in A Dialogue Agaynst Light, Lewde, and Lascivious Dauncing, Christopher Fetherston contends, ‘Whereas is wanton dauncing, there the Divell daunceth also’ (1582: sig. D2r). But was the reverse also believed to be true? Did having the Devil present guarantee that any dancing that occurred would be wanton? What about for those who were already damned? When witches, devils, and demons danced, did they necessarily dance in an unchaste, immodest manner? If not, how did their dancing differ from that of the general populace?

[4] This paper investigates these questions by examining and contextualizing dance scenes featuring witches in three Jacobean and Caroline plays: Thomas Middleton’s The Witch, William Shakespeare and Middleton’s Macbeth, and Richard Brome and Thomas Heywood’s The Late Lancashire Witches. Although plays were under no obligation to depict dance realistically, spectators needed to be able to recognise staged dancing as dancing. Thus, even staged dances described as strange or spectacular would likely still resemble conventional dancing in most aspects. Moreover, while there are no extant records that detail the precise steps and floor patterns for these dances, the stage directions and surrounding text provide clues to the style of movement used and how it might have mirrored or diverged from the steps and styling described in the surviving dance instruction manuals of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as well as in other archival and literary records. In addition to their implications for staging dancing in modern productions of these plays, that many sources stress the ‘strangeness’ of witches’ dancing rather than its lewdness offers an important reminder that early modern communities found witches and witchcraft threatening for a multitude of reasons, not just for aberrant or unbridled sexuality.[ii]

A Note on Dates

[5] Because early modern plays were typically written and performed years if not centuries before they were printed, dating can be difficult. Richard Brome and Thomas Heywood’s The Late Lancashire Witches is quite unusual in that it was written, performed, and printed in the same year, 1634, whilst the titular witches were awaiting trial in London (Findlay 2002: 146). The dating of The Witch is more typical in its ambiguity. Because of the play’s allusions to the Thomas Overbury affair, most scholars date the writing of The Witch to between 1613 and 1616, leaning towards 1616, which is when Frances Howard and Robert Carr were found guilty at the much-followed trial for Overbury’s murder (he had been Carr’s secretary and had opposed the marriage to Howard after the annulment of her prior marriage) (Shakespeare 1999: 156; Middleton 2007: 1128). The only known written copy of The Witch dates from sometime after 1619, but the play was not published until 1778 (Shakespeare 1999: 156; Middleton 1986: 13).

[6] Dating for Macbeth is even more difficult to pin down. The scholarly consensus is that William Shakespeare wrote Macbeth, and the play was likely first performed, in 1606, while the only early printed text is found in the First Folio, published in 1623 (Shakespeare 1999: 6, 156). However, Thomas Middleton seems to have revised the play, perhaps substantially, around 1616, adding two of the songs from The Witch—‘Come away, come away’ and ‘Black spirits’—to the scene in Macbeth in which the witches dance, additions which the First Folio retains (Shakespeare 2017: 2999–3000; Cutts 1956: 203).This means that when discussing the dancing of the witches in Macbeth, one is discussing a play written by both Shakespeare and Middleton, making comparisons with similar scenes in The Witch essential.

[7] In addition, as Anne Daye has argued, when examining the witches’ scenes in Macbeth as c.1616 instead of c.1606, the influence of the antimasque of witches in Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Queens (1609) becomes clear: Macbeth’s witches use a similar rhythm for charms and incantations as Jonson’s witches, and both the masque and the play utilize configurations of three and nine (2019: 121). While neither includes choreographic instructions, Daye notes that the meter of the chants in both works matches that of doubles, a traveling step sequence of three paces and a close, which is described in surviving dance instruction manuals (2019: 121). Thus, not only is it likely that ‘The witches of Macbeth may also have incorporated basic dance steps with their speeches in 1.1 and 4.1’, as Daye contends, but connecting staged dances in plays with those in court masques makes turning to European dance instruction manuals for choreographic suggestions that much more defensible (2019: 121).

Dance Instruction Materials

[8] There is some evidence of a pan-European dance culture, especially among elites. Dancing masters travelled around Europe teaching at different courts and schools, travellers took dancing lessons when visiting other countries, and libraries and book inventories include dance instruction manuals from different countries. Regional variants were likely, and it is difficult to know how closely the galliard danced by Elizabeth I in England matched the galliard described in French or Italian manuals (Ravelhofer 2016: 16–36; Nevile 2018: 102–17; Smith and Gatiss 1986: 201).

[9] Nevertheless, the surviving manuals preserve steps and choreographies that would have otherwise been lost and enable modern-day reconstructions. (See Monahin’s Source List.) Manuals describe individual steps such as singles and doubles, floor patterns such as figure eights and hays, and choreographies for different dance types such as the processional pavane, the rustic branle, and the athletic galliard. Several also include accompanying music, illustrations, and notes on dancefloor etiquette. While they are not comprehensive in their coverage—courtly dance types are described more frequently and in greater detail than the dances of those of lower rank and status—these manuals greatly increase our ability to conceive of what was meant when other sources mention dancing in passing.

[10] In addition, by outlining the conventions and expectations of dancing in this period—dance steps begin on the left foot unless otherwise specified; both men and women can lead a dance or ask a partner to dance; the height of jumps and kicks should take into account the dancer’s gender and rank, not just strength and agility; women should not lift their skirts to show off fancy footwork, etc.—the extant manuals also give us a sense of what unconventional or aberrant dancing might have entailed (Winerock 2011: 455–7).

Ben Jonson’s Antimasque of Witches in The Masque of Queens (1609)

[11] In addition to the extant dancing manuals, the most illuminating source when considering how witches might have danced on the seventeenth-century English stage is Ben Jonson’s description of the antimasque of witches in The Masque of Queens (1609). The antimasque contains two dances choreographed by Jerome Herne. The second dance is of particular interest thanks to Jonson’s detailed notes and explanations. Witches ‘at their meetings do all things contrary to the custom of men, dancing back to back, hip to hip, their hands joined, and making their circles backward to the left hand, with strange fantastic motions of their heads and bodies’ (Jonson 1979: 330). After sprinkling a potion on the ground and in the air, the witches go around and around until ‘a strange and sudden music’ is heard, at which point ‘they fell into a magical dance full of preposterous change and gesticulation’ (Jonson 1979: 330).

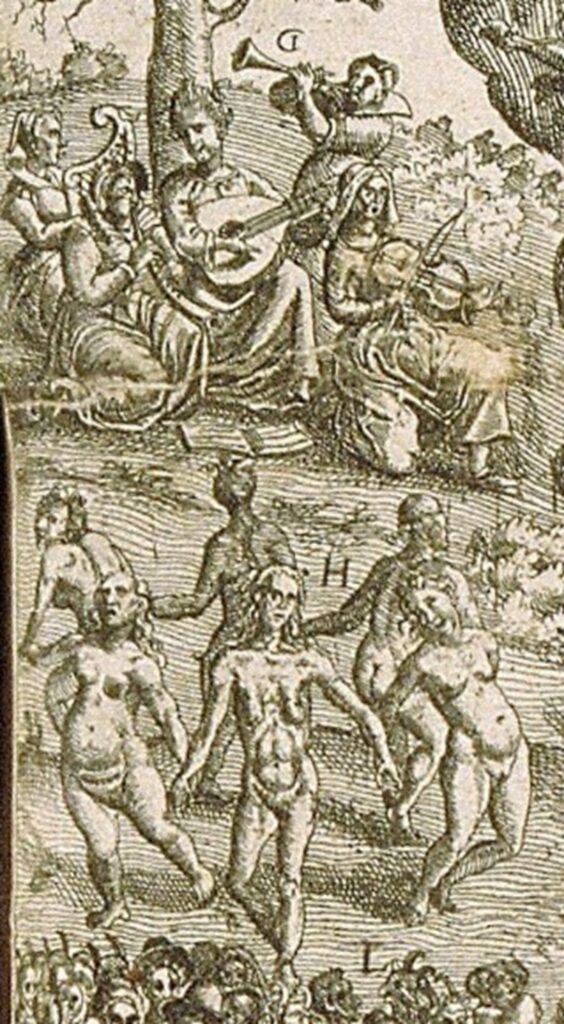

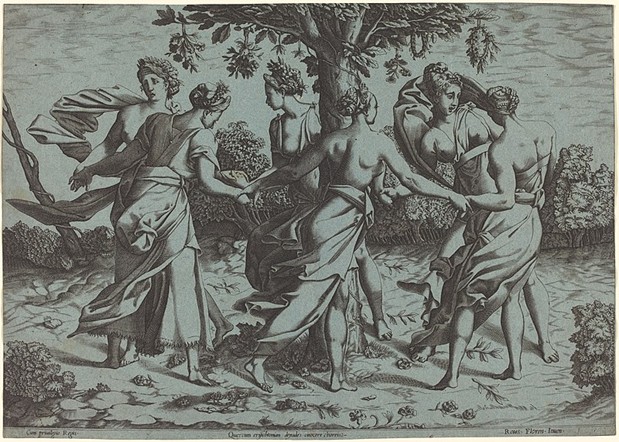

[12] Both courtly and country repertoires included circle dances, but images, as well as choreographic descriptions, always depict the dancers facing into the circle (See Figs. 2, 3). To an early modern viewer, having all the dancers facing out from the circle would have immediately signalled that a dance was unusual or ‘unnatural’. As Alessandro Arcangeli contends in his analysis of Nicolas Rémy’s treatise Daemonolatria (1595), Rémy describes witches dancing back-to-back in rings and circles to emphasise ‘a choreography ruled by inversion’ (Arcangeli 2017: 85). Rémy also speculates that facing out from the circle, like wearing a mask to the Sabbath, might serve the practical purpose of hiding the participants’ identities, as well, ‘preventing the devil’s followers from recognizing one another if brought to trial’ (Arcangeli 2017: 85). Still, Rémy primarily stresses the oddity and strangeness of these practices—witches ‘love to do everything in a ridiculous and unseemly manner’—and sees their dancing as another manifestation of their tendency to ‘behave in a manner opposite to that of other men’ (Arcangeli 2017: 85, 86).

[13] Jonson’s description of the witches’ antimasque stresses the dissonance and oddity of their movement. In his introductory notes, he even calls it ‘a spectacle of strangeness’ (Jonson 1979: 321). Diane Purkiss has argued that rather than embodying any particular definition of witchcraft (popular, humanist, classical, etc.), Jonson’s witches are a ‘muddle of otherness’ (Purkiss 1996: 203). Yet, choreographically, these witches move in a manner consistent with descriptions of the witches’ Sabbath in European continental demonologies (see below). The witches demonstrate their inversion of all things good and holy by literally inverting and reversing Renaissance dance conventions: they dance back-to-back, move widdershins (that is counterclockwise) instead of clockwise, and make strange gestures with their heads and bodies instead of keeping them gracefully and elegantly upright.[iii] If the masque did indeed influence later plays such as The Witch, The Late Lancashire Witches, and the revised Macbeth, then Herne and Jonson’s choreographic choices, however briefly notated by Jonson, help support Anne Daye’s assertion that The Masque of Queens helped bring English ideas about witchcraft more in line with Scottish and continental conceptions (2019: 121). Moreover, as Amanda Eubanks Winkler has observed, not only had Herne’s choreography ‘encapsulated common ideas about witches’ terpsichorean practices, ideas that can be seen in virtually all seventeenth-century depictions of witches’ round dancing, theatrical and otherwise’, but it retained its relevance for quite some time: ‘witches in the anti-witchcraft tract The Kingdom of Darkness (1688) still dance a round, back-to-back’, holding hands (2006: 30).

[14] Jonson does not include a full choreography with precise steps and figures aligned to music in his account of the masque, but the choreographic details that he does offer highlight what made the witches’ dance distinctive from other masque dances and are sufficient for creating historically-informed stagings for modern productions that can convey those distinctions. Still, the specificity and utility of Jonson’s choreographic hints are not always appreciated. For example, Purkiss helpfully notes that ‘preposterous literally means having in front what should come behind’, but then she interprets metaphorically what I would read as Jonson’s literal description of the witches’ movements as characterised by ‘preposterous change and gesticulation’, asserting, ‘Here preposterousness is part of a general display of reversal and inversion’ (1996: 203).

[15] The strangeness and discordance of the witches’ dancing is also mirrored in the music, preserved in Robert Dowland’s Varietie of Lute-lessons (1610). The first witches’ dance is mostly dissonant, with elongated passages that likely accompanied gestures (See Audio Clip 1). The second witches’ dance alternates the dissonant, gestural accompaniments with more regular, danceable passages. As Amanda Eubanks Winkler notes, in between the ‘rhythmically regular’ first and third sections of the piece, ‘expectations are subverted as the rhythmic pattern is disturbed’, and the metrical changes create ‘a musical analogue to the witches’ jerky, strange, and unpredictable movements described by Jonson (2006: 31) (See Audio Clip 2). Following Anne Daye’s method of matching music and movement, one could interpret the gestural passages choreographically to strongly emphasise the witches’ grotesque strangeness, while pairing the more rhythmically even passages with more typical dance sequences with just a few unconventional touches, such as the back-to-back orientation Jonson mentions in his description (Daye and Barlow 2003: 85). Highlighting the ‘strangeness’ of witches’ dancing also accords well with the handful of descriptions found in witchcraft trial records and treatises.

Audio Clips 1 and 2: Excerpt from “The Witches’ Dance” No. 1 and No. 2 by Robert Johnson. Performed by Dorothy and Bertram Barth, YouTube, 2019. https://youtu.be/bFHnE92iUB4.

Treatises and Trial Records

[16] European treatises on witchcraft and trial court records provide ample details on feasting and fornicating with the Devil, but witches’ dancing is less well-described, at least until the end of the sixteenth century when demonologists and prosecutors became interested in dance as a component of the witches’ Sabbath (Arcangeli 2017: 84). Nevertheless, the sources that do mention dance offer vivid, if brief, descriptions.

[17] Lambert Daneau’s 1564 description of dancing at the witches’ Sabbath is typical. Daneau was a French Calvinist theologian and a ‘rigorous proponent of a Puritan lifestyle’, so he was not favourably disposed towards dancing in general (Ganzer and Steimer 2004: 92). That makes his passage on witches’ dancing all the more interesting, quoted here from A Dialogue of Witches, the 1575 English translation attributed to Thomas Twyne. At the witches’ Sabbath, Satan, appearing as ‘a most filthy bucke goate’, either leads the witches in a dance, or ‘els they hoppe and daunce merely about him, singing most filthy songes made in his prayse’ (Daneau 1575: sig. F7v). Although Daneau does not give much choreographic detail, a led dance implies a line dance or processional dance, while ‘they hoppe and daunce’ around the Devil, could indicate a circular dance with hops and kicks such as a branle or country dance. Regardless, by calling it ‘hopping’, Daneau suggests that this dancing is more energetic than stately.

[18] Daneau also specifies that the witches provide their own musical accompaniment for their dancing by singing. The songs are described as ‘filthy’, but there is little indication that the movements that accompanied them were similarly obscene.[iv] While it is possible that the witches could incorporate sexually suggestive gestures or pantomime into their dance, this is not a male-female couple dance like the vast majority of early modern choreographies (Winerock 2011: 458, 475). Rather it is either single sex, with the (presumably female) witches dancing together, or has one male, Satan, leading all of the women. Practically speaking, these configurations would limit the options for actual male-female sexual activity within the dance. Regardless, this dancing is decidedly celebratory: the witches dance following their confirmation of their oath to Satan, and the accompanying songs are ‘made in his prayse’.

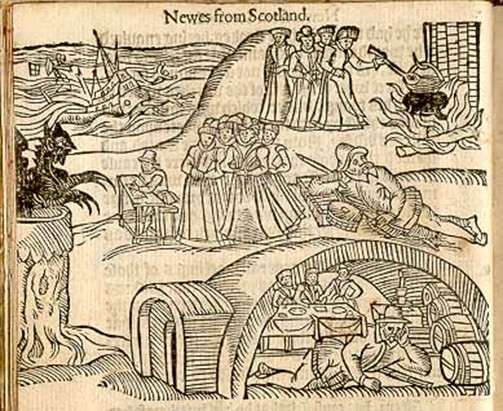

[19] Testimonies in the account of the life and death of Doctor Fian, who was burned as a sorcerer in Edinburgh in 1592, provide another glimpse of witches’ dancing.[v] Doctor Fian and a large number of witches were accused of bewitching and trying to drown James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) at sea. According to the account given in Newes from Scotland (1592), at the trial, one of the accused witches, Agnes Tompson, explained that dancing was a component of the bewitchment ritual.[vi] Tompson reported that on All Hollow’s Eve, she and about two hundred other witches went by sea to the kirk of North Berwick in Lowthian, and, ‘after they had landed, tooke handes on the land and daunced this reill [reel] or short daunce, singing all with one voice’ (Carmichael 1592: sig. A3r). Tompson added that Geillis Duncan ‘did goe before them playing this reill or daunce vpon a small Trump, called a Iewes Trump, vntill they entred into the Kerk of north Barrick’ (Carmichael 1592: sig. A3v). The reel was an old Scottish dance with a circular travelling figure (Collinson 2001). The King attended the trial hearings and found Tompson’s testimony particularly fascinating. He even invited Geillis Duncan to court to demonstrate the dance song that she and the others had performed as part of their ritual, although as Diane Purkiss has observed, the dramatically different context of this encore would have altered its meaning, robbing it of any ‘occult significance’ and shifting Duncan’s role from leader to entertainer (Purkiss 1996: 200).

[20] Unfortunately, the images that accompany Newes from Scotland do not show the witches dancing, but it is notable that they depict the witches as ordinary-looking women wearing conventional attire and having proper, almost pious bearing (See Figs. 4, 5). The modest demeanour of the women in the illustration and the fact that the two hundred dancers were all women create an image of order and propriety that makes Tompson’s account of the witches’ ‘pennance’ in the church following the dancing that much more shocking. In an inversion of a proper, holy oath, the witches kiss the Devil’s buttocks instead of his hand or foot as he leans over the pulpit of the church (Carmichael 1592: sig. A3v).

[21] One of the only descriptions of a witches’ Sabbath from an English source, a pamphlet entitled The vvonderfull discouerie of witches in the countie of Lancaster (1613) by Thomas Potts, features a similar juxtaposition of dancing and shocking interactions with demonic creatures. Pott was the court clerk at the witches’ trial in Lancaster and created the pamphlet at the judges’ request (Gowing 2004). In his account, drawn selectively from the trial records, a fourteen-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, reported that on several Thursday and Sunday nights, she, her grandmother, her aunt, and another woman were carried by ‘foure black things, going upright, and yet not like men in the face’ across a river to feast on strange meat, dance, and have sex with demons. Sowerbutts explained, ‘after they had eaten, the said three Women and this Examinate danced, euery one of them with one of the black things aforesaid’ (Potts 1613: sig. L2v). After dancing, the women engaged in some form of sexual activity with the mysterious creatures, although it is not clear how consensual these activities were:

After their dancing the said black things did pull downe the said three Women, and did abuse their bodies, as this Examinate thinketh, for shee saith, that the black thing that was with her, did abuse her bodie (Potts 1613: sig. L2v).

Interestingly, Sowerbutts, who claimed to be bewitched by the other women, described herself as engaging in the same activities as the ‘true’ witches. Marion Gibson argues that Sowerbutts’ participation in these rites, even while bewitched, collapsed distinctions between victim and witch and helped to cast doubt on the veracity of her account (102). Her inability to explain why the other women would want to bewitch her and the ‘lurid, continental-style testimony’ that characterised her description of the witches’ Sabbath prompted additional scepticism (Pumfrey 2002: 35). Under questioning, Sowerbutts admitted that she had been encouraged to make the accusations and coached on what to say by a Jesuit priest hiding in the area, who was also the uncle of one of the accused witches (Pumfrey 2002: 35). Subsequent interrogations revealed a complex situation with families split by religious differences and fears and suspicions fuelled by recent deaths in the community (Hasted 1993: 30–3). Eventually, the three accused witches were exonerated. However, the trial attracted a great deal of attention and generated pamphlets and ballads that contributed to the dissemination, and eventual embracing, of this more ‘continental’ conception of the witches’ Sabbath that, ironically, at the trial had raised the judges’ suspicions.

[22] Daneau, Carmichael, and Pott’s accounts all feature descriptions of women dancing alongside references to ‘most filthy’ songs, kissing of buttocks, and sex with demons, creating an association between witches’ dancing and general depravity. Yet, importantly, there is no accusation or even insinuation in these sources that the dancing itself was lewd. As Lynneth Miller Renberg observes in Women, Dance, and Parish Religion in England, 1300–1600, it was not sexual sins that most closely linked female dancing and witchcraft in medieval and Renaissance Europe, but the sins of rebellion, sacrilege, and idolatry (Renberg 2022: 98).

Visual Evidence: Lancre’s Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et démons (1613) and Gauzzo’s Compendium Maleficarum (1608)

[23] One of the only demonologies that claimed that witches’ dancing was lascivious was Pierre de Lancre’s Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et démons (1613). De Lancre was a French judge and demonologist who instigated France’s largest and most notorious witch hunt in 1609 in the Pays de Labourd region on the French-Spanish border (Maus de Rolley and Machielsen 2020: 283). As Margaret McGowan observes wryly, ‘no account ever rivalled Lancre’s in his prodigious joy of discovery and in his profound horror at what he revealed’ (1977: 197). De Lancre’s treatise, which stresses the ‘inconstancy’ of witches and demons, also offers one of the most detailed descriptions of dancing at a witches’ Sabbath.

[24] De Lancre’s beliefs about witches’ dancing—that it is sexually suggestive, as well as disorderly and unnatural—build on his convictions that all contemporary dancing, but especially the dances favoured by the Basque and the Spanish, like the ‘lewd and shameless’ saraband, ‘stir up and torment the body’ with illicit sexual desires (2006: 218–9). Like many antidance commentators, he acknowledges that there are some dances, such as those of the French noble court, that are more decorous, and he lauds the ‘virile and energetic’ dancing of ancient civilisations even as he decries their degeneration into the ‘cowardly steps’ and ‘delicious vanity’ of contemporary dancing (de Lancre 2006: 218–9; also Pennino-Baskerville 1991, Wagner 1997). That being said, de Lancre stresses that the dancing of witches at the Sabbath was ‘even dirtier and more depraved’ than the already reprehensible social dances of his own day. Indeed, some of de Lancre’s claims are quite extraordinary: witches dance ‘wearing nothing but their shirts, with a large cat attached to their behinds’, and the ground upon which they dance becomes cursed and ‘no grass or any other thing can grow there’ (2006: 220, 226).

[25] Other assertions sound more familiar, such as that witches often dance in a circle back-to-back, a configuration that de Lancre finds deeply offensive, at least when it is done by male-female or demon-witch couples (2006: 225). Holding hands with their backs to each other, de Lancre explains, the dancers ‘come so close together that they touch each other and have their backs touch each other, every man touching a woman. And, dancing to a certain beat, they bump each other and wantonly bring their backsides up against each other’ (2006: 225). The repetition in the description of the dancers’ backs and bottoms touching each other conveys de Lancre’s shock and horror that dancers would have more bodily contact than handholding. He also contends that ‘the lame, crippled, and old decrepit people and the almost dead’ are able to dance with ease at the Sabbath, ‘because these are celebrations of disorder, where everything appears to be irregular and to be going against the laws of nature’ (2006: 225).

[26] And yet, despite de Lancre’s adamant insistence that the dancing of witches was scandalously wanton, the engraving by Jan Ziarnko that illustrates the activities of the witches’ Sabbath does not show, or even strongly suggest, lewd dancing.[vii] The image features two groups of dancers. (See Fig. 6) In both groups, the dancing witches are naked, but they do not touch each other or their demon partners beyond holding hands. We do not see the bumping backsides in de Lancre’s text. One group of dancers is all women, who vary somewhat in body shape, age, and attractiveness. That they are dancers is confirmed by the musicians who play instruments behind them (See Fig. 7). The dancers face outwards from the circle, matching the description in the text, and departing from customary practice for both country and courtly dances of the period, as discussed above.

[27] The second group of dancers in the engraving also features mostly naked, female witches, but here they are dancing with demons. (See Fig. 8). They dance around a tree, as if it were a maypole, and the witches and demons alternate, just as in depictions of regular circle dances, where the women and men alternate (See Figs. 2, 3 above).

[28] In Ziarnko’s second group of dancers, however, the witches face into the circle, while the demons face outwards, another variation on inverting circle-dance conventions. Yet, while this image could be suggesting a perversion of a maypole dance, since none of the witches and demons is looking at each other, there is no sexual energy, no hint of attraction or seduction. The handholds in the group with the demons are more varied than in the group of all-female dancers, but again, this does not seem to suggest wantonness as much as variety—the dancers seem to be caught up in the motion of the dance, rather than communicating sexual attraction for, or interest in, one another.

[29] Whilst facing out from the circle might subtly suggest a dance ‘in a manner opposite to that of other men’, it is the dancers’ nakedness that is likely the first aspect the viewer notices about the witches’ dance in Sabbat des Sorciers. The absence of clothing signals aberrance and suggests impropriety. Yet, on closer inspection, the dance does not seem particularly wanton: the dancers hold hands in the customary fashion at the customary distance one would expect for a circle dance. There is no bumping or rubbing of backsides, no untoward touching. In other words, the artist has chosen to depict some aspects of de Lancre’s description, but not others. Thus, it is possible to read the nakedness of the dancers as more of an inversion of propriety rather than as evidence of wanton dancing, similar to how their dancing back-to-back is presented as an inversion of the custom of dancing facing into the circle rather than as an opportunity to rub backsides.

[30] Francesco Maria Guazzo’s Compendium Maleficarum (1608) has a woodcut that also depicts witches and devils dancing. Guazzo, an Italian demonologist and brother of the Order of St. Ambrose, mostly summarises others’ arguments and information about witches in his treatise, but the woodcuts that illustrate the pact with the Devil include distinctive depictions of dancing (Levack 2015: 107) (See Fig. 9).

[31] There are a few noteworthy differences compared to the Ziarnko engraving: there are both male and female witches, all the humans are clothed, and all the dancers face into the circle. Here we might expect to see more sexual suggestiveness, and yet the dancers are just as far apart as before, and the only dancers making eye contact are the man and woman next to each other in the foreground. The only aspect of this dance that is unusual is the presence of demons among the dancers; otherwise, this reads as a perfectly ordinary, proper circle dance. We do not even see the ‘lack of civilité’ that often characterised depictions of dancing by marginal groups (Arcangeli 2017: 90). Rather, Michelle Brock’s observation about the dancing of witches and the Devil in Scotland seems to hold true across Europe: ‘despite his apparent ability to harm, the Devil found in witchcraft cases was rarely monstrous or obviously frightening’ (2016: 160). Instead, encounters with the Devil were characterised by their ‘surprising ordinariness’; in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Europe, ‘Even dancing with the Devil was a tame affair’ (Brock 2016: 160).

Thomas Middleton’s The Witch (c.1616)

[32] Today, the most familiar seventeenth-century scene with dancing witches is Act IV, Scene 1 of Macbeth, but this scene’s songs, and perhaps dances, likely originated in Thomas Middleton’s The Witch and were added to Macbeth by Middleton when he revised the play around 1616 (see ‘A Note on Dates’ above). Set at the ducal court in Urbino, Middleton’s witches threaten the community, not because they are inherently evil, but because members of the community seek their aid to charm, curse, or otherwise alter the natural feelings and reactions of their neighbours.

[33] While some of Middleton’s witch scenes highlight the magic of the theatre, with stage effects and machinery enabling the witches to take flight, it is the music and dancing in Act V, Scene 2 that makes this witch scene memorable. The setting is Hecate’s cave, a remote place to which other characters must journey to seek favours from the witches. The dancing is preceded by a charm sung while the witches mix a potion in a cauldron. The stage directions only say, ‘Here they dance The Witches’ Dance and exeunt’, but the witches mention a round in the text, and sing the song, ‘Black Spirits’, whose lyrics, as noted above, have a very danceable rhythm, so there may have been multiple circle-based dances in this scene (5.2.84SD). The music does not survive, but Ross W. Duffin has suggested Packington’s Pound as a possible tune and includes an evocative recording of this setting in the audio recording that accompanies Shakespeare’s Songbook (2004: 65–7, Track 5) (See Audio Clip 3).

Audio Clip 3. ‘Black Spirits’, Track 5, CD accompanying Shakespeare’s Songbook by Ross Duffin. Performed by Ellen Hargis, Judith Malafronte, and Custer LaRue, W.W. Norton & Co., 2004, Azica Records, 2010, YouTube by NAXOS of America, 2015. https://youtu.be/R9XoZiiXJAY.

[34] The witches do not play instruments to create the music to accompany their dancing but instead bring forth music supernaturally in this scene, another component that Middleton transfers over to Macbeth. Hecate proclaims, ‘Come, my sweet sisters. Let the air strike our tune / Whilst we show reverence to yond peeping moon’ (5.2.83–4). ‘Reverence’ is an interesting choice of words here, because it was also the name of the bow used in dancing (See Fig. 10). Moreover, this ‘reverence’ points us to a possible difference in the plays’ dance scenes. Whereas The Witch witches dance to honour the moon and ‘all ill’, the Macbeth witches explain that they will dance to entertain Macbeth and lift his spirits (The Witch 5.2.68; Macbeth 4.1.143–4).

[35] There are five dancing witches, plus Hecate, in The Witch, which offers many choreographic options,[viii] although the staging likely borrowed from Jonson and Herne’s aforementioned antimasque of witches, which was performed just a few years prior in 1609.[ix] That the witches dance to honour the moon emphasises their ‘lunacy’ or strangeness. This is worth stressing because earlier in the play, dancing is referred to alongside lust and wantonness. In Act 1, Scene 2, Hecate describes what witches do while flying at night:

When hundred leagues in air we feast and sing,

Dance, kiss and coll, use everything.

What young man can we wish to pleasure us

But we enjoy him in an incubus? (1.2.28–31)

At first glance, Hecate seems to be including dance among a list of lascivious activities that witches indulge in such as kissing and colling (that is, embracing). However, this list also includes feasting and singing. I would argue that dancing is simply included here as one of the activities that witches find enjoyable.

[36] This view of dancing—as possibly enticing, but not inherently wanton—parallels that expounded by characters in the play who are not witches. In Act II, Scene 2, when Amoretta is briefly bewitched by a love charm, she says of Almachildes:

There’s not a sweeter gentleman in court;

Nobly descended too, and dances well.

Beshrew my heart, I’ll take him when there’s time. (2.2.45–7)

Here, a woman includes dancing skilfully as part of a young man’s allurements that make her desire him, but there is no indication that he dances in a sexually suggestive manner.

[37] Both the dance scene and the dance references in The Witch present dancing as an inherently enjoyable activity. To the extent that this dancing is problematic, it is because it represents indulging in one’s desires generally, not because the dancing itself is illicit or sexually explicit. Dancing causes lust only in those who are inclined towards it already.

Shakespeare and Middleton’s Macbeth (c.1606, c.1616, pub.1623)

[38] Whereas the courtiers who seek the services of witches in Middleton’s The Witch are primarily concerned with romantic and sexual desires, in Macbeth, it is the desire for political power that brings lords such as Macbeth to consult with witches. Nevertheless, since witchcraft can help fulfil diverse desires, and dancing accompanies charm creation as well as conveys witches’ inherent strangeness, Middleton was able to transpose much of the witches’ dance scene from The Witch to Macbeth.

[39] In Act IV, Scene 1 of Macbeth, the three witches, or weird sisters, perform a dance to rouse and entertain Macbeth, who has fallen into a stupor in response to the apparitions the witches have shown him. The unhelpfully laconic stage directions merely state: ‘The Witches dance and vanish’, but the preceding lines offer a few more details (4.1.148SD). Noting that Macbeth stands ‘amazedly’, the First Witch suggests:

Come, sisters, cheer we up his sprites

And show the best of our delights.

I’ll charm the air to give a sound

While you perform your antic round,

That this great king may kindly say

Our duties did his welcome pay. (4.1.143–8)

As Lucy Munro has observed, in the late Renaissance, in addition to meaning ‘grotesque, disorderly, and foolish’, the term ‘antic’ also had performative associations that extended to gestures and postures, facial expressions, and clothing (2015: 78). Thus, when the First Witch suggests performing an ‘antic round’, she leads the audience to expect ‘self-consciously performed bodily disorder, signalled through movement, facial expression, and costume’ (Munro 2015: 78). Other comic and otherworldly characters such as clowns, fairies, nymphs, and angels were usually depicted dancing in circles as well, sometimes facing into the circle following convention, sometimes facing outwards to emphasise their ‘unnaturalness’ or ‘supernaturalness’ (See Figs. 11, 12).

Indeed, the words of the song ‘Black Spirits’ that Hecate and the witches sing at the beginning of the scene compare the witches’ dancing to that of fairies and elves: ‘And now about the cauldron sing / Like elves and fairies in a ring’ (4.1.41-42). While there are some ambiguities—does the First Witch dance in addition to providing the music?—the text provides a few choreographic clues to guide staging. We have an overall floor pattern—a ring or circle—and a performance style—antic or grotesque.[x] We have textual support for the dancers circling the cauldron, as mentioned in the song that opens the scene. As to whether the dancing should be sexy or strange, this would be a clear-cut case for strangeness.

[40] Another staging option is to have the witches circle Macbeth whilst they sing and dance. As Richard Brathwaite writes in his guide to proper conduct for gentlewomen, ‘in the opinion of the Learned’, dancing is considered, ‘the Divels procession: Where the Dance is the Circle, whose centre is the Devil’ (Brathwaite 1631: 77). Placing Macbeth at the centre of a witches’ dance foreshadows his descent into truly devilish acts and suggests that rather than bewitching or enchanting him, the witches are merely facilitators of Macbeth’s own dark desires.

Richard Brome and Thomas Heywood’s The Late Lancashire Witches (1634)

[41] Richard Brome and Thomas Heywood’s The Late Lancashire Witches was written, performed by the King’s Men, and published in 1634, while actual accused witches from Lancashire were in London, awaiting trial (Findlay 2002: 146). Interestingly, although the outcome of the trial was still unknown at the time, the playwrights wrote from the perspective that the witches were guilty (Findlay 2002: 149). Thus, the staging of their dancing would have reflected contemporary assumptions about how witches danced, rather than used movement to cast doubt on the veracity of the accusations.

[42] One way that the play emphasises the true ‘witchiness’ of the witches is by contrasting their dancing with that of the other villagers. In Act III, Scene 3, guests at the wedding of the servants Lawrence and Parnell call for a dance, and the fiddlers begin to play ‘Sellenger’s Round’, a well-known dance tune popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. John Playford’s The Dancing Master includes choreographic instructions, as well as the tune (1657: 132) (See Video Clip 1).

[43] However, when the musicians start to play, there are problems: first they play a different tune than the one the dancers were expecting; then each musician starts playing a different tune at the same time, creating a cacophonous din; on the third attempt, their instruments make no sound at all, and the guests begin to suspect witchcraft.

[44] Witchcraft is indeed the cause for the musical mayhem, but a piper has conveniently arrived, and ‘no witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire bagpipe, for itself is able to charm the devil’ (3.3.548). Doughty requests a ‘lusty hornpipe’ and invites ‘all into the dance—nay, young and old’ (3.3.549).[xi] The stage directions call for a dance, with the note that the bride and bridegroom ‘reele in the daunce’ (3.3.549SD). Brett Hirsch has explored the ambiguity as to whether this ‘reel’ refers to the Scottish dance often mentioned alongside hornpipes and jigs, or to stumbling about as the result of bewitchment, but either way, at the dance’s end, the guests’ suspicions are confirmed (2013: 140–2).[xii] As the rest shout ‘Bravely performed!’, the servant, Mall Spencer, and the piper vanish, causing her suitor, Doughty, to reflect, ‘Now do I plainly perceive again, here has been nothing but witchery all this day’ (3.3.550, 553).

[45] Hornpipe references date from around 1480 through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Pforsich 1998: 377). Thus, at the time of the play’s performance, both dances named in this scene, ‘Sellenger’s Round’ and the hornpipe, were well-known old dances associated with traditional pastimes and celebrations, and while both could be danced in couples, neither were particularly associated with lewdness or wantonness.[xiii] In other words, these traditional dances, and the nuptials they celebrate, represent the kind of well-regulated, orderly yet festive community that the witches want to destroy.

[46] The second dance scene, Act IV, Scene 1, follows closely upon the first, but the scene has shifted from a house in town in the afternoon to an old barn in the countryside at night. Spirits serve a feast, and then the witches call for music and dancing. Goody Dickieson requests:

You, our familiars, come.

In speech let all be dumb,

And to close up our feast,

To welcome every guest,

A merry round let’s dance. (4.1.601)

Meg then calls for dance music:

Some music then i’th’ air

Whilst thus by pair and pair

We nimbly foot it. Strike! (4.1.602)

As music plays, Mall observes, ‘We are obeyd’, and one of the Spirits finishes out the rhyme in response: ‘And we hels ministers shall lend our aid’ (4.1508–9). The stage directions then indicate: ‘Dance and Song together’ (4.1509SD).

[47] In terms of staging for this scene, there are many options and few certainties. Goody Dickieson calls for a ‘round’, that is, a circular dance. Going ‘paire and paire’ could mean that the witches dance in pairs with their familiars or just with each other. The dance is accompanied by a song, but it is not clear who sings it—it could be one or all of the spirits, all of the dancers, or someone offstage. That the dance is described as ‘merry’ and that the dancers ‘nimbly foote it’ suggests an upbeat tempo with hops, skips, and fast or fancy footwork.

[48] Indeed, the ‘merriness’ of the dancing is central to the play’s tone overall and shaped the impression of spectators. Upon seeing the play in the theatre in 1634, Nathaniel Tomkyns complained that it lacked ‘poetical genius’ but that he, nevertheless, enjoyed the ‘odd passages and fopperies’ and the ‘divers songs and dances’, concluding that ‘it passeth for a merry and excellent new play’ (2020). The witches are happy to intervene in their neighbours’ sex lives, causing the groom to be impotent on his wedding night and interrupting the dancing at the wedding that symbolises love and marital harmony. However, in their own dancing, it is the witches’ strangeness that is emphasised, not sexual impropriety.

Conclusion

[49] In late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century England, the long-established association of dance with the Devil expanded to include dancing witches: ‘true’ witches danced to celebrate the triumph of evil and utilised dancing in their magical ceremonies and rituals. The characteristics of witches’ dancing, however, were not universally agreed upon. A few continental demonologists such as Pierre de Lancre described it as notably indecent and contended that dancing at the Sabbath was one of the Devil’s preferred methods to rouse ‘base and filthy desires’ in young virgins (2006: 218). Yet, for most English authors and commentators, the concerns about wanton dancing expressed in sermons and antidance treatises do not seem to have extended to those, such as witches, who were already damned. Evidence from illustrations, masques, and plays indicates that people imagined witches’ dancing as primarily strange and antic. Rather than displaying a complete rejection of propriety and morality when depicting dancing witches on the page and on the stage, playwrights and performers seem to have restricted themselves to inversions of Renaissance dance conventions: dancing back-to-back, moving counterclockwise, and utilising grotesque rather than graceful gestures, posture, and styling. In other words, descriptions of and references to English witches’ dancing exemplify what Robin Briggs terms the only ‘partial inversion’ of early modern witchcraft (2007: 146).

[50] Seventeenth-century playgoers like Nathaniel Tomkyns clearly enjoyed scenes of witches dancing, but they may also have found them unsettling. The character of Mall Spencer in The Late Lancashire Witches embodies a real fear: What if some witches were not old, ugly, and mean, bore witches’ marks, and always danced back-to-back? Mall is young, beautiful, and charming, and although she cavorts grotesquely at the witches’ Sabbath, she can dance a hornpipe just as gracefully, or saucily, as the other servant girls when she wants to. Early modern communities desperately wanted to be able to easily and reliably identify witches in their midst, and while lewd dancing might be sinful, it was hardly restricted to the Devil’s followers (Winerock 2012: 92–4). The emphasis on the distinctive ‘strangeness’ of witches’ dancing in masques and plays like The Masque of Queens, The Witch, Macbeth, and The Late Lancashire Witches may reflect wishful thinking that witches’ motions could and would reveal their deviance.

NOTES

[i] The Devil’s kiss or osculum infame (‘kiss of shame’) entailed kissing the Devil’s anus and was considered ‘the ultimate act of abasement’ (Guiley 2008: 192).

[ii] I would like to thank the members of the Dance Studies Association’s Early Dance Working Group and the generous readers and reviewers of this article for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors and infelicities are, of course, my own.

[iii] One confusing aspect is that Jonson clearly describes the witches moving to the left in a circle. Arcangeli, for example, describes moving clockwise or ‘to the left’ as both customary and an inversion (85). The distinction seems to be the dancers’ orientation. If the dancers are facing into the circle, as is customary, then moving ‘to the left’ is clockwise. This is the instruction found in Arbeau’s Orchésographie (1581) for branles danced in circles (Sutton 1996: vol. 1, 522–3). However, if the dancers face outwards, as the witches are described as doing, then ‘to the left’ is counterclockwise, which gets read as unusual or strange.

[iv] While ‘filthy’ could simply mean ‘dirty’ in this period, from the 1530s on, it was also used to denote moral foulness, immorality, and obscenity, such as the ballads sung to ‘filthie tunes’ in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Pt 1, II.ii.45 (‘filthy, adj., no., and adv., OED 2016).

[v] The source, Newes from Scotland (1592), is usually attributed to James Carmichael, a Church of Scotland minister and scholar, who also served as a judge in ecclesiastical cases and appears to have been involved in the witch trials, including compiling the witches’ depositions (Cameron 2004).

[vi] Here I refer to the accused witch who mentions dancing as Agnes Tompson, since that is the name given in the source quoted, Newes from Scotland. However, in the original trial records, the woman who provided this testimony was Agnes Sampson, although an Agnes Tompson is mentioned elsewhere in the records (Normand and Roberts 2000: 312, 325; for more about Agnes Sampson, also see Willumsen 2022: 142–57).

[vii] The Ziarnko engraving was added in the second edition of the work. It did not accompany the 1612 first edition (Maus de Rolley and Machielsen 2020: 283).

[viii] For choreographic figures representing a moon, star, serpent’s-tongue, and salamander, among others, for five or six dancers, see Nevile 2018: 89, 179–81.

[ix] Daye provides extensive analysis of the antimasque of witches, including suggestions for staging the dances, in her dissertation chapter ‘The Masque of Queens 1609: Launching the Antimasque Venture’ (2008: 109–66). Cutts suggests that The Witch might have transposed the choreography and music from the antimasque (1960: 115–6). However, Winkler points out that since the witches’ coven is not dispelled in the play, the meaning of the dance, even if it looked and sounded similar, would be different than in the masque: order is not entirely restored; the threat from the witches remains (2006: 34).

[x] When Simon Forman saw Macbeth in 1611, he described the three women who prophesise that Macbeth will become a king as ‘fairies or nymphs’ rather than witches or hags (Shakespeare 1999: 154). However, since a circle or round was also the configuration associated with fairy dances, a circular staging would still work in what we now think of as the witches’ scenes even if these characters were more nymph than witch prior to Middleton’s revisions.

[xi] No hornpipe choreographies survive from this period, but textual and musical references indicate it had a 3/2 or 4/4 rhythm, was particularly associated with Lancashire and northern England, Wales, and Scotland, and was traditionally accompanied by bagpipes (Winerock 2012: 46, 78–80; Pforsich 1998: 375–7).

[xii] See also Pendlebury 2015.

[xiii] In addition to the aforementioned Spanish saraband, the French volta, a courtly couple dance that included a turning lift, and the English cushion dance, a dance game that included kissing different partners while kneeling on a cushion, would be examples of more risqué dances (Winerock 2012: 71–5, 312–6). While ‘dancing’ was sometimes used as a euphemism for sexual intercourse, this use for the phrase ‘dancing “Sellenger’s Round”’ is mostly found in the latter half of the seventeenth century (Green 2010).

WORKS CITED

Arbeau, Thoinot. 1967. Orchesography. (Orchésographie, 1589), trans. by Mary S. Evans, ed. by Julia Sutton (New York: Dover).

Arcangeli, Alessandro. 1994. ‘Dance under Trial: The Moral Debate 1200–1600’, Dance Research, 12.2: 127–55.

———. 2017. ‘The Savage, the Peasant, and the Witch’, European Drama and Performance Studies, 8: 71–91.

Babington, Gervase. 1583. A very fruitfull exposition of the Commaundements (London).

Blécourt, Willem de. 2013. ‘Sabbath Stories: Towards a New History of Witches’ Assemblies’, in The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America, ed. by Brian Levack (Oxford: Oxford University Press): pp. 84–100.

Brathwaite, Richard. 1631. The English gentlevvoman (London).

Briggs, Robin. 2007. The Witches of Loraine (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Brock, Michelle. 2016. Satan and the Scots: The Devil in Post-Reformation Scotland, c.1560–1700 (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate).

Cameron, James K. 2004. ‘Carmichael, James (1542/3–1628), Church of Scotland minister and scholar’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/4701 [accessed 9 November 2022].

Carmichael, James. 1592. Newes from Scotland, declaring the damnable life and death of Doctor Fian a notable sorcerer, who was burned at Edenbrough in Ianuary last. 1591. (London).

Collinson, Francis. 2001. ‘Reel’, in Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.23050 [accessed 6 June 2023].

Cutts, John. 1956. ‘The Original Music to Middleton’s The Witch’, Shakespeare Quarterly, 7.2: 203–9.

———. 1960. ‘Robert Johnson and the Court Masque’, Music and Letters, 41: 111–26.

Daneau, Lambert. 1575. A dialogue of witches, in foretime named lot-tellers, and now commonly called sorcerers (De venificis quos olim sortilegos, nunc autem autem vulgo sortarios vocant, dialogus, 1564), trans. by [Thomas Twyne] (London).

Daye, Anne. 2008. ‘The Jacobean Antimasque within the Masque Context: A Dance Perspective’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Roehampton University, University of Surrey).

———. 2019. ‘“The revellers are entering”: Shakespeare and Masquing Practice in Tudor and Stuart England’, in The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Dance, ed. by Lynsey McCulloch and Brandon Shaw (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 107–31.

Daye, Anne, and Jeremy Barlow. 2003. ‘The Shock of the New: Ben Jonson’s antimasque of witches 1609’, On Common Ground 4: Reconstruction and Re-creation in Dance before 1850 (Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire: DHDS Publications): pp. 83–94.

de Lancre, Pierre. 2006. On the Inconstance of Witches: Pierre de Lancre’s Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et demons (1612), trans. by Harriet Stone and Gerhild Scholz Williams (Tempe, Arizona: ACMRS, BREPOLS).

Duffin, Ross W. 2004. Shakespeare’s Songbook, with Audio CD (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Co.).

Fetherston, Christopher. 1582. A dialogue agaynst light, lewde, and lasciuious dauncing(London).

Findlay, Alison. 2002. ‘Sexual and Spiritual Politics in the Events of 1633–34 and The Late Lancashire Witches’, in The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, ed. by Robert Poole (Manchester: Manchester University Press): pp. 146–65.

Forrest, John. 1999. The History of Morris Dancing, 1458–1750 (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co).

Ganzer, Klaus, and Bruno Steimer, eds. 2004. Dictionary of the Reformation, trans. by Brian McNeil (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company).

Gibson, Marion. 1999. Reading Witchcraft: Stories of Early English Witches (London: Routledge).

Gowing, Laura. 2004. ‘Pendle witches Lancashire witches (act. 1612)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/67763 [accessed 9 November 2022].

Green, Jonathon. 2010. ‘dance, v.’, in Green’s Dictionary of Slang https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/zn4nn5y [accessed 9 November 2022].

Guazzo, Francesco Maria. 1608. Compendium Maleficarum(Milan).

Guiley, Rosemary. 2008. The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft, and Wicca (New York: Facts on File, Inc.).

Hasted, Rachel. 1993. The Pendle Witch Trial 1612 (Preston: Lancashire County Books).

Hirsch, Brett. 2013. ‘Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux?’ Early Theatre 16.1: 139–49.

Jonson, Ben. 1979. The Masque of Queens (1609), in Ben Jonson’s Plays and Masques, ed. by Robert M. Adams (New York: Norton & Company): pp. 321–40.

Levack, Brian, ed. 2015. The Witchcraft Sourcebook (London: Routledge).

Maus de Rolley, and Jan Machielsen. 2020. ‘Pierre de Lancre’s Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et démons’, in The Science of Demons: Early Modern Authors Facing Witchcraft and the Devil, ed. by Jan Machielsen (London and New York: Routledge): pp. 283–98.

Maxwell-Stuart, P. G. 2020. ‘A Royal Witch Theorist: James VI’s Daemonologie’, in The Science of Demons: Early Modern Authors Facing Witchcraft and the Devil, ed. by Jan Machielsen (London and New York: Routledge): pp. 165–78./p>

Middleton, Thomas. 1986. The Witch, in Three Jacobean Witchcraft Plays, ed. by Peter Corbin and Douglas Sedge (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

———. 2007, 2012. The Witch, ed. by Marion O’Connor, in Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works, ed. by Gary Taylor, John Lavagnino, MacDonald P. Jackson, John Jowett, Valerie Wayne, and Adrian Weiss (Oxford: Oxford University Press): vol. 1, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780199580538.book.1 [accessed 19 May 2023].

Munro, Lucy. 2015. ‘Antique / Antic: Archaism, Neologism and the Play of Shakespeare’s Words in Love’s Labour’s Lost and 2 Henry IV’, in Shakespeare’s World of Words, ed. by Paul Yachnin (London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare): pp. 77–102.

Nevile, Jennifer. 2018. Footprints of the Dance: An Early Seventeenth-Century Dance Master’s Notebook (Leiden: Brill).

Normand, Lawrence, and Gareth Roberts. 2000. Witchcraft in Early Modern Scotland: James’ VI’s Demonology and the North Berwick Witches (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press).

Northbrooke, John. 1577. Spiritus est vicarius Christi in terra. A treatise wherein dicing, dauncing, vaine playes or enterluds with other idle pastimes [et]c. commonly vsed on the Sabboth day, are reproued by the authoritie of the word of God and auntient writers (London).

Pendlebury, Celia. 2015. ‘Jigs, Reels, and Hornpipes: A History of “Traditional” Dance Tunes of Britain and Ireland’ (unpublished master’s dissertation, University of Sheffield).

Pennino-Baskerville, Mary. 1991. ‘Terpsichore Reviled: Antidance Tracts in Elizabethan England’, Sixteenth Century Journal, 22.3: 475–94.

Pforsich, Janis. 1998. ‘Hornpipe’, in International Encyclopedia of Dance, ed. by Selma Jeanne Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press): vol. 3, pp. 375–7.

Playford, John. 1657. The Dancing Master: or, plain and easie Rules for the Dancing of Country-Dances, 3rd edition (London).

Pumfrey, Stephen. 2002. ‘Potts, Plots, and Politics: James I’s Daemonologie and The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches’, in The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, ed. by Robert Poole (Manchester: Manchester University Press): pp. 22–41.

Purkiss, Diane. 1996. The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-Century Representations (London and New York: Routledge).

Ravelhofer, Barbara. 2006. The Early Stuart Masque: Dance, Costume, and Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Renberg, Lynneth Miller. 2022. Women, Dance, and Parish Religion in England, 1300–1640 (Woodbridge and Rochester: Boydell).

Shakespeare, William. 1999. Macbeth: Texts and Contexts, ed. by William C. Carroll (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s).

———. 2017. Macbeth, ed. by John Howett, in The New Oxford Shakespeare: Critical Reference Edition, ed. by Gary Taylor, John Jowett, Terri Bourus, and Gabriel Egan (Oxford: Oxford University Press): vol 2, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198759560.book.1 [accessed 19 May 2023].

———. 2003. Macbeth, ed. by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine (Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library) https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/macbeth/ [accessed 7 June 2022].

Smith, Judy, and Ian Gatiss. 1986. ‘What Did Prince Henry Do with His Feet on Sunday 19 August 1604?’, Early Music 14.2: 198–207.

Stubbes, Phillip. 1583. The anatomie of abuses (London).

Sutton, Julia. 1998. ‘Branle’, in International Encyclopedia of Dance: A Project of Dance Perspectives Foundation, Inc., ed. by Selma Jeanne Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press): vol. 1, pp. 520–4.

Tomkyns, Nathaniel. 2020. ‘Letter of 16 August 1634 to Sir Robert Phelips in Somerset’, quoted from ‘Stage Histories for The Late Lancashire Witches’, ed. by Elizabeth Schafer, in Richard Brome Online https://www.dhi.ac.uk/brome/history.jsp?play=LW [accessed 7 June 2022].

Wagner, Ann. 1997. Adversaries of Dance: From the Puritans to the Present (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press).

Williams, Gordon. 2001. A Dictionary of Sexual Language and Imagery in Shakespearean and Stuart Literature (London: Athlone Press).

Willumsen, Liv Helene. 2022. The Voices of Women in Witchcraft Trials: Northern Europe (London and New York: Routledge).

Winerock, Emily. 2011. ‘“Performing” Gender and Status on the Dance Floor in Early Modern England’, in Worth and Repute: Valuing Gender in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Essays in Honour of Barbara Todd), ed. by Kim Kippen and Lori Woods (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies): pp. 449–72.

———. 2012. ‘Reformation and Revelry: The Practices and Politics of Dancing in Early Modern England, c.1550–c.1640’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto) https://hdl.handle.net/1807/34965 [accessed 7 June 2022].

Winkler, Amanda Eubanks. 2006. O Let Us Howle Some Heavy Note: Music for Witches, the Melancholic, and the Mad on the Seventeenth-Century Stage (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press).